Cartography of Narratives

GROUP SHOW

Mar 31, 2019 - Apr 14, 2019

- SELECTED WORKS

- CURATORIAL NOTE

- REVIEWS

- PRESS RELEASE

- DOWNLOAD CATALOGUE

What does civilisation contain but disjointed lived experiences of passing temperaments. Through evidential remnants, phantom memories and oral narratives, contemporary mythopoesis issues out of empirical notions, experiences and sustained gestures. Interspersed with the physical, the architectural and the natural, the ‘Cartography of Narratives’ becomes a mapping of the lived, imagined and the oneiric, that clutch within its framework, hints to aspects of reality. The panorama is structured on a network of consequences, with possible contingencies determined by their causal relationships. Fact and fiction become ambiguous entities.

While history can be viewed in the light of factual evidences of a recent past, mythology, contained within fictional configurations, harks back to primeval times. What amount of truth lies in contemporary reiterations of these historical chronicles, without an element of fiction? While history on the one hand is selective, on the other, as a result of repeated iterations, it becomes a fabrication over due course.Roland Barthes in Mythologies (1957), his key contribution to the semiology of the process of myth creation, remarks, “what the world supplies to myth is an historical reality, defined, even if this goes back quite a while, by the way in which men have produced or used it; and what myth gives in return is a natural image of this reality.”

As elucidated by Romila Thapar in The Historian and Her Craft (2018), historical tradition is based on two related aspects, the ‘purpose of action’ and the ‘agency of action’. While the purpose of action is weighed with evidences to validate the aim of events in history, the agency rests in who and what regulates this history and its outcome as a historical truth. In the case of myths, Thapar describes it as a form of “utterance”, one that is handed down through cultural, religious and community rites, becoming an intrinsic part of our everyday conduct and continuing to resurface and perform their role in current social and political situations. With civilisations and societies organized around them, culture-specific myths often disclose the structure beneath ideologies, superstitions and the very thought process.

CURATORIAL NOTE

What does civilisation contain but disjointed lived experiences of passing temperaments. Through evidential remnants, phantom memories and oral narratives, contemporary mythopoesis issues out of empirical notions, experiences and sustained gestures. Interspersed with the physical, the architectural and the natural, the ‘Cartography of Narratives’ becomes a mapping of the lived, imagined and the oneiric, that clutch within its framework, hints to aspects of reality. The panorama is structured on a network of consequences, with possible contingencies determined by their causal relationships. Fact and fiction become ambiguous entities.

While history can be viewed in the light of factual evidences of a recent past, mythology, contained within fictional configurations, harks back to primeval times. What amount of truth lies in contemporary reiterations of these historical chronicles, without an element of fiction? While history on the one hand is selective, on the other, as a result of repeated iterations, it becomes a fabrication over due course.Roland Barthes in Mythologies (1957), his key contribution to the semiology of the process of myth creation, remarks, “what the world supplies to myth is an historical reality, defined, even if this goes back quite a while, by the way in which men have produced or used it; and what myth gives in return is a natural image of this reality.”

As elucidated by Romila Thapar in The Historian and Her Craft (2018), historical tradition is based on two related aspects, the ‘purpose of action’ and the ‘agency of action’. While the purpose of action is weighed with evidences to validate the aim of events in history, the agency rests in who and what regulates this history and its outcome as a historical truth. In the case of myths, Thapar describes it as a form of “utterance”, one that is handed down through cultural, religious and community rites, becoming an intrinsic part of our everyday conduct and continuing to resurface and perform their role in current social and political situations. With civilisations and societies organized around them, culture-specific myths often disclose the structure beneath ideologies, superstitions and the very thought process.

Mythology, fantasy and fiction become elements catered to in order to reimagine a past. The purpose and intention that produce mythologies are numerous, founded on personal and collective or communitarian conceptions about an unintelligible past. Grand narratives, creation tales, and origin myths raised within magical landscapes of nature and culture, may tend to delineate a significant past or an idea through metaphors and analogies. Mythology becomes a transmission of memory through oral systems or the written tradition, and when performed time and again, contributes to the historical timeline. This process helps the thrusting of this community knowledge from one generation to the next.As Barthes argues, “ancient or not, mythology can only have an historical foundation, for myth is a type of speech chosen by history: it cannot possibly evolve from the ‘nature’ of things.”

Barthes elucidates how ‘myth is a type of speech’, a form of language developed within special conditions in order to become a myth, subsequently a ‘system of communication’ and a ‘mode of signification.’ A myth is a semiological narration, that transforms every object into an oral state through descriptive language. The object becomes the signifier of meanings and through numerous interpretations, the signified is subsequently consumed. Language is replete with biases, notions, imaginings, concepts and opinions, manifesting in to a variety of myths and perpetuating the convention of mythmaking.

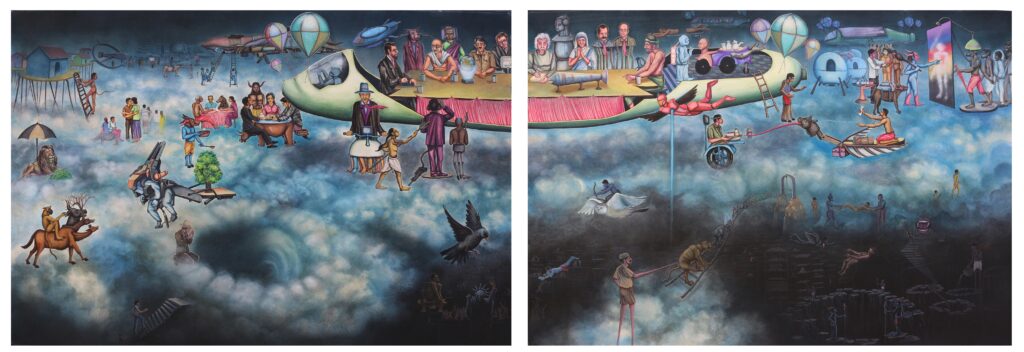

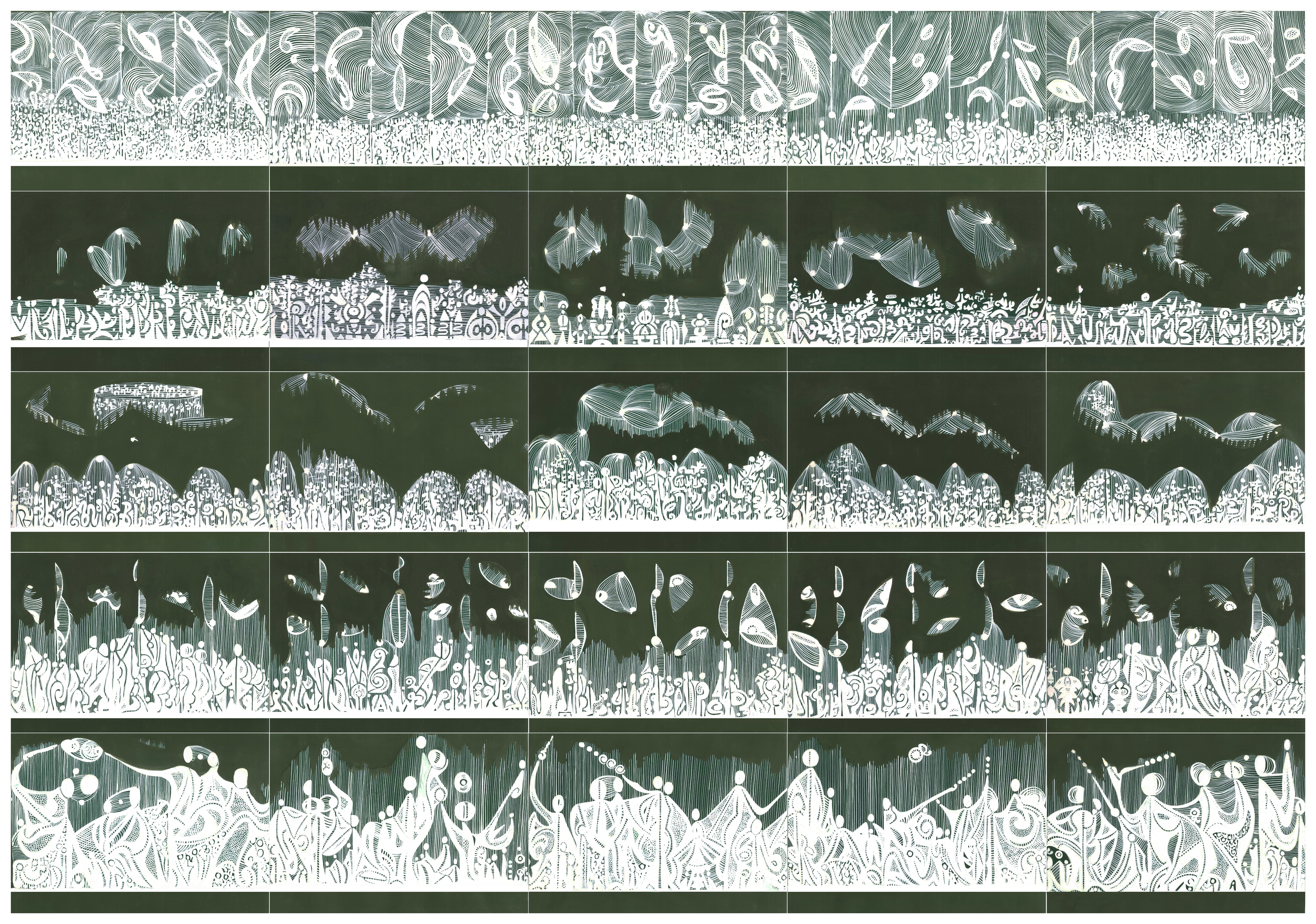

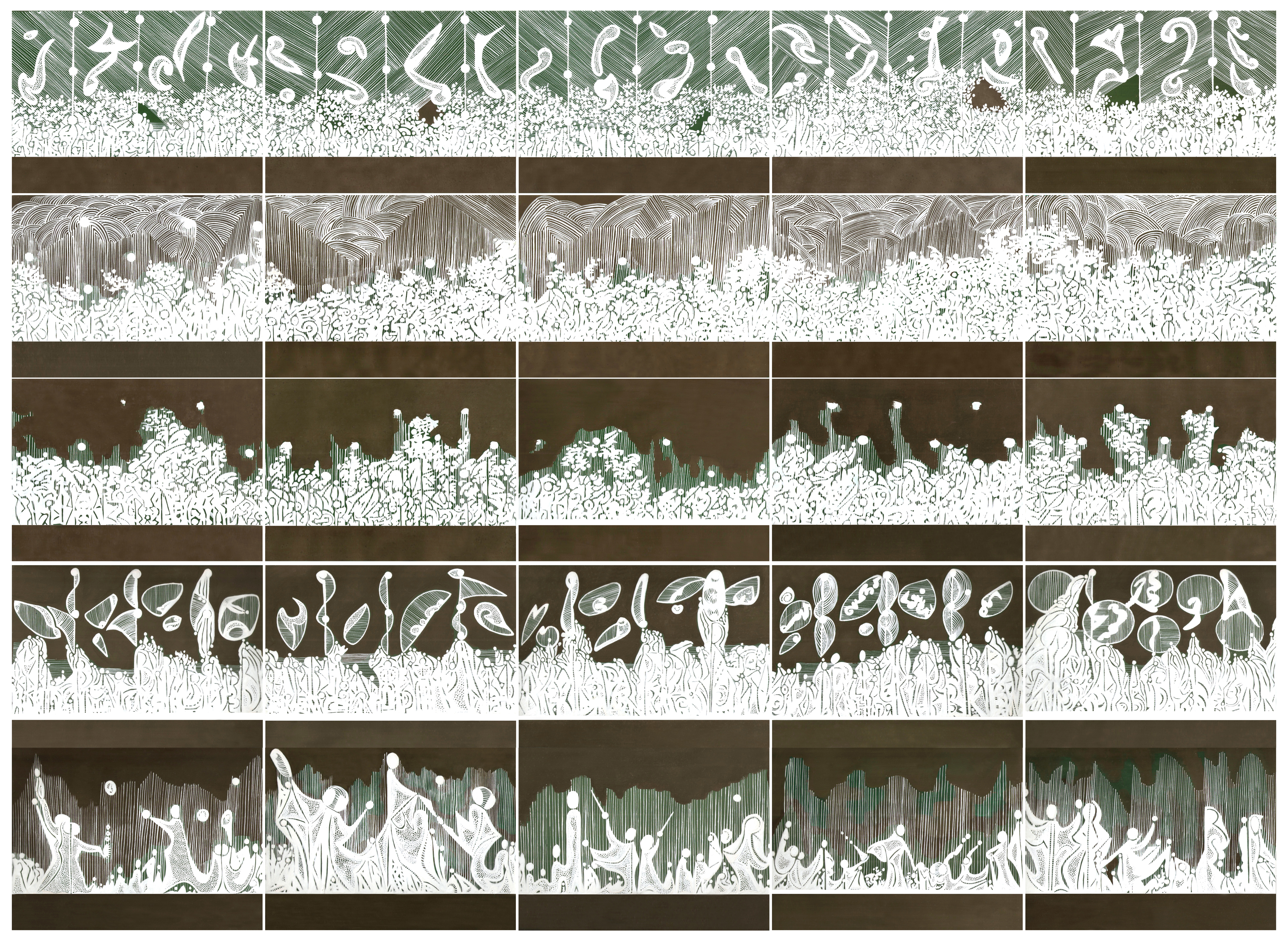

Participating artists such as Subrat Kumar Behera with his diptych Hell of a Paradise, attempts to look at how myth and mythological narratives get constructed and interpreted in contemporary times. Through the representation of ‘hell’ and ‘paradise’ within a dystopic landscape, he employs various metaphors and iconic imageries to comment on the present condition of the world.

On a similar note, Sanket Viramgami’s Myths of Modern Life exercises the technique of miniature painting and Kantha art, camouflages the surroundings into a surreal space and depicts a landscape that is constantly changing. His work reflects the overall viewpoint of the world around him. Taking inspiration from Panchatantra stories, fables and myths, Sanket also attempts to depict his personal journey from the rural to the urban cityscape.

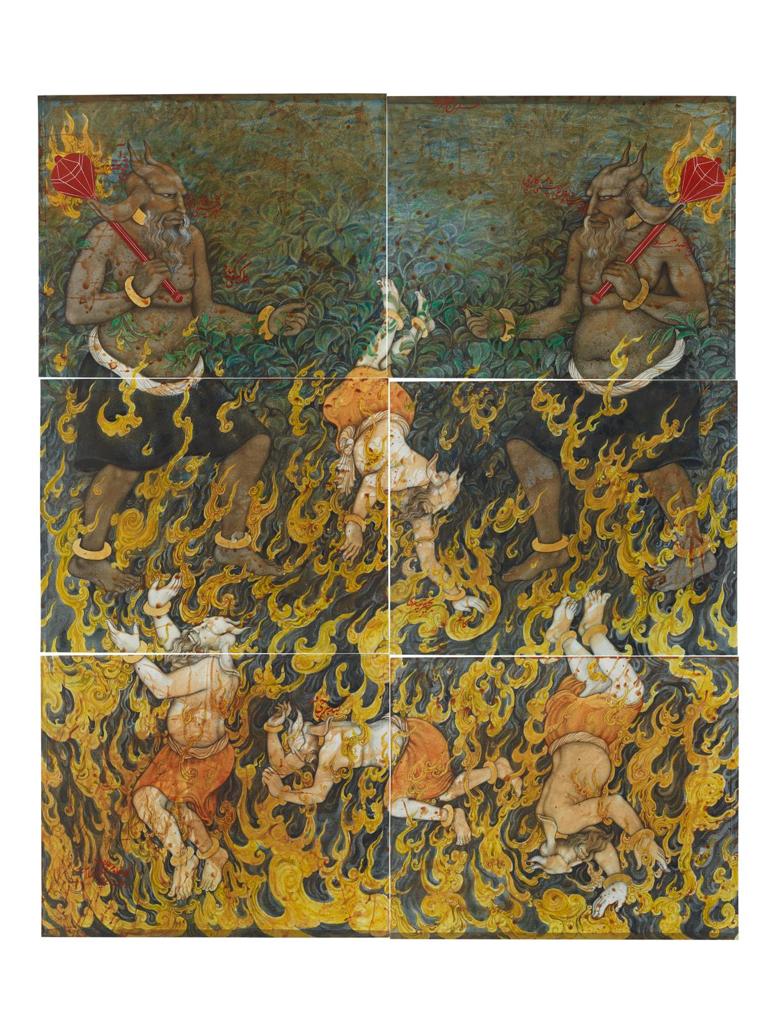

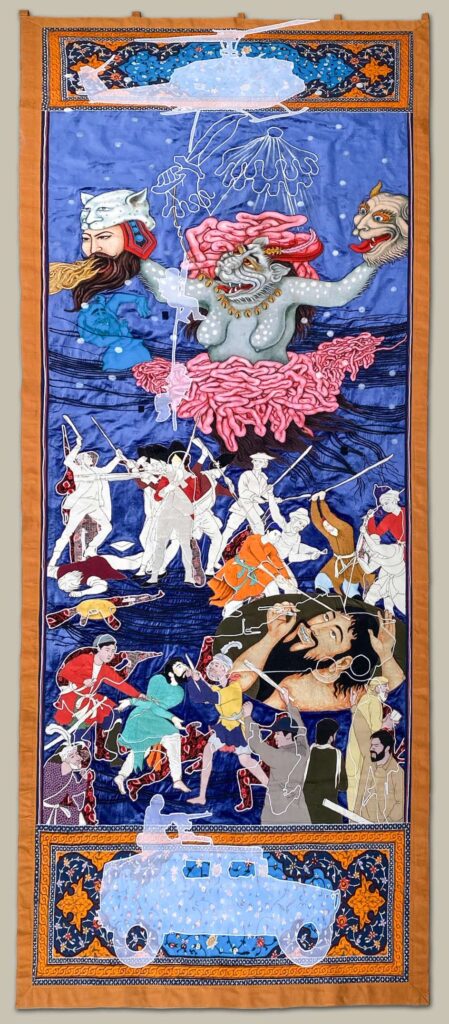

The Hazara artist Khadim Ali on the other hand, exploits the seductive aesthetic of Persian miniature painting to inflect contemporary concerns. Taking the 10th -11th century Persian epic Shahnameh as his point of departure, he presents a complicated characterization of the residents of its pages such as Rostam, Sohrab and Esfandiyar, tracing their persistence and renewed significance in present times. Ali’s paintings tell stories about loss (of his own cultural heritage and of human values) and about how meaning shifts as words and images are perverted through ideological appropriation. Taking from the pages of the Shahnameh, he traces the nature of friends and foes, self and others, the victor and the victim.

While in the process of passing down histories, they are open to filtering out, adding on, imagination and/or reinterpretation of details. At this juncture,the concept of ‘postmemory’ might serve some purpose to the aspects discussed. Postmemory isa set of experiences transmitted from generation to generation, causing their progeny to become the carriers of this ‘invisible’ history and a delayed experience. As described by Marianne Hirschin her essay The Generation of Postmemory (2012), it is the relationship between generations, that remember through the witnessing and transmitting of memories of personal experiences, stories, images and behaviors. “Postmemory’s connection to the past is thus not actually mediated by recall but by imaginative investment, projection, and creation. To grow up with such overwhelming inherited memories, to be dominated by narratives that preceded one’s birth or one’s consciousness, is to risk having one’s own stories and experiences displaced, even evacuated, by those of a previous generation,”she argues.

Art history is derived from the remnants of lived experiences and ‘artistic’ production. What we gather as art historical knowledge comes from an intended or unintended cultural production of artefacts that now serve their purpose in private collections, institutions or museums. But with art today largely catering to an art market, artistic production becomes a conscious and purposeful gesture, contributing in the process, to the making of a parallel historical timeline. A work of art on its production becomes immediate history, that decades later may add to the course of art historical research and level with art historical discoveries.How much of history is fabricated within the course of contemporary mythmaking? Who is held responsible for the making these histories?

Working within this narrative framework, Pakistani artist Waseem Ahmed’s series of works are based on the current social and political issues and incidents that have affected his artistic pursuit. Employing the traditional miniature style, he depicts these harsh realities using images from the past to show how stories of war and conflict remain the same, while only the names change. His inspiration mostly comes from people he interacts with on an everyday basis and their views regarding society and politics. The artist observes how these people change with the changing social, religious and political times to create a common ground between their opinions and the ideas of intellectuals.

In his earliest works Jagannath Panda experimented with different media on paper, mixing collage and drawing techniques to explore the role of iconography in communication and to comment upon socio-political situations in contemporary India. Using his signature technique of incorporating traditional brocade fabrics onto surfaces, his series Shifting Horizon resembles the skin of beasts, the bark of trees or the garments of mythological figures. His works are often lifted directly from the epic Hindu sagas of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata.

Moving onto urban narratives exhibiting the physical and psychical dilemmas within the changing aspects of the civilization, artistslikeNoor Ali Chagani presentshis sculptural work titled Janamaz. It is a prayer mat made of terracotta bricks is an attempt to comment, through the choice of material, on the environment he lives within. It becomes a gesture of surrendering oneself to these bricks, its influence, hunger and its endless greed. Chagani weaves the bricks together to transform the rigid character of the bricks to that of a soft, flexible rug. With this, he comments on the preconceived notions of rigidity, identity and ownership.

Gigi Scaria’s series of works, ComfortZone is reminiscent of the continuous tussle between nature and humans, to create a modern urban landscape. His works attempt to address the blindness of humanity towards the depletion of natural resources and environmental disasters, thereby, providing a new prism to ponder upon the idea of a smart city.

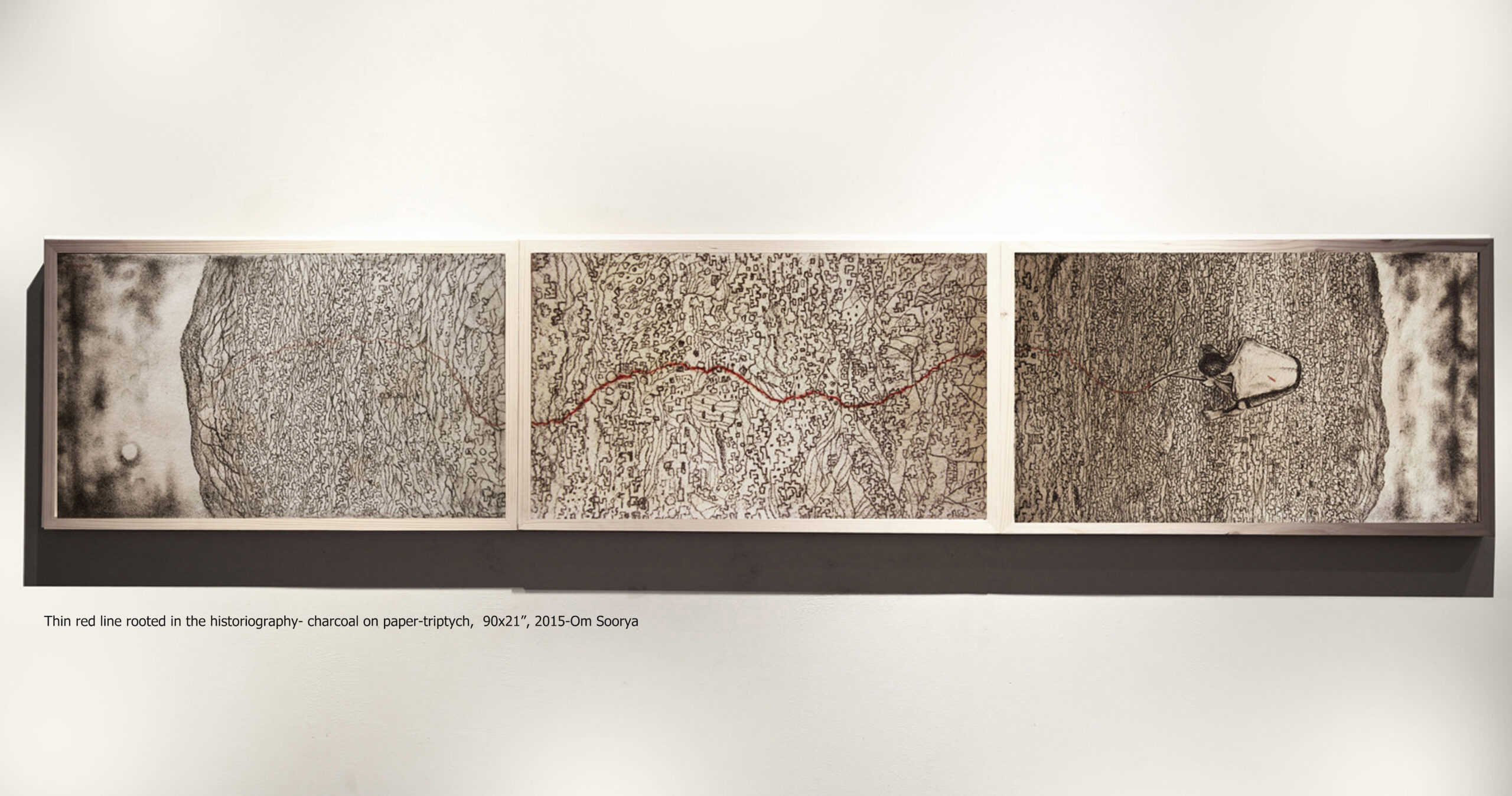

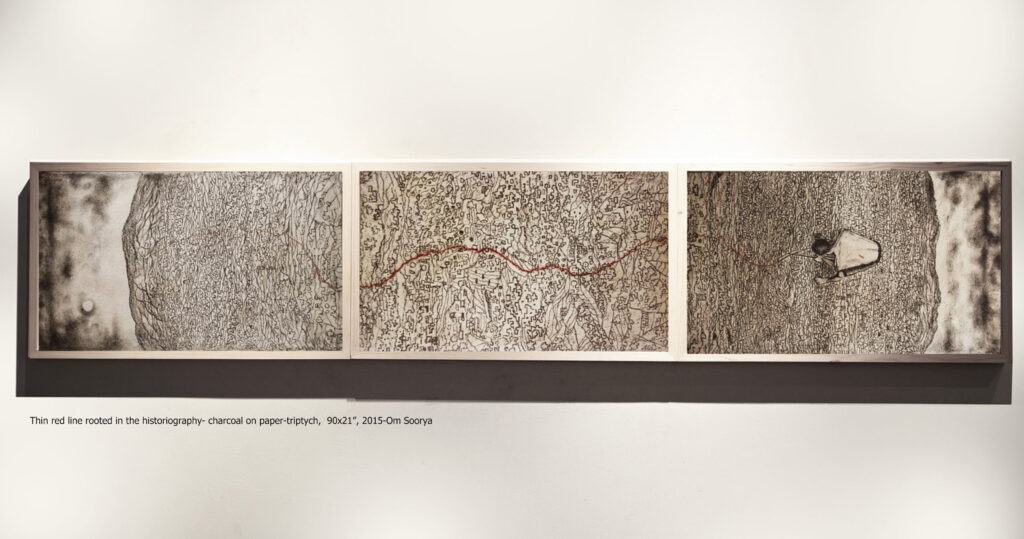

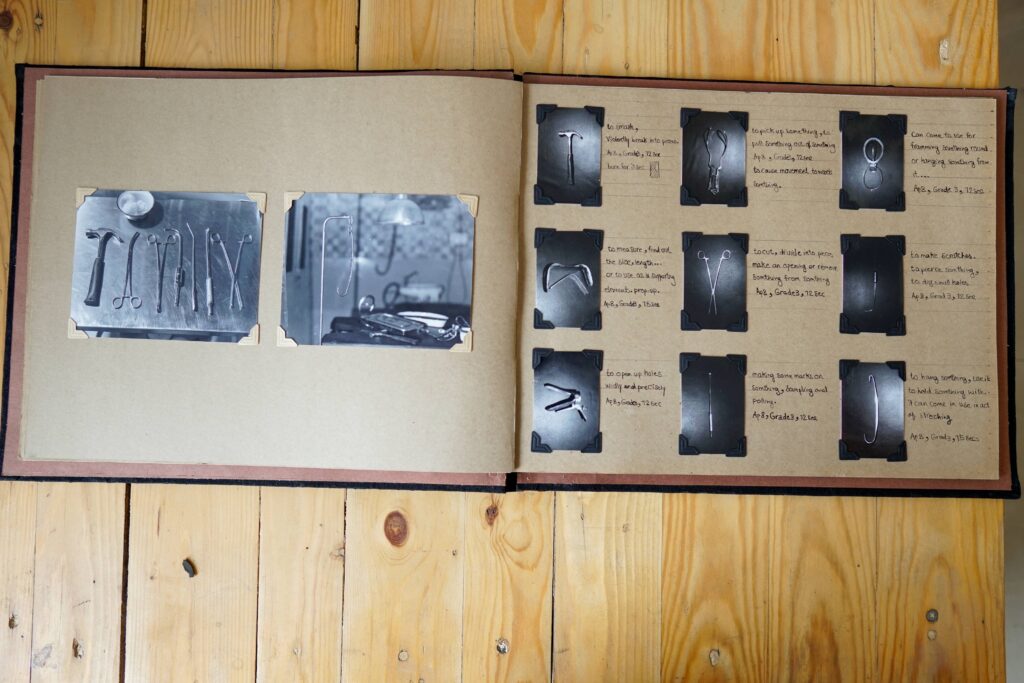

The Thin Red Line by Om Soorya examines the struggles of marginalised individuals against the hierarchical practices of the Indian society. These individuals have never otherwise been a part of the mainstream historiography of India.His drawings should primarily be seen as maps of conceptual relationships between historiography and geography. These drawings are a representation of the struggle of subaltern groups.

Reviving the dream argument by René Descartes that advocates that there are no definite signs to distinguish dream experience from waking reality, the artists also attempt to illuminate upon the various mental landscapes through a staged composition that is influenced from their personal remembrances and mental states.

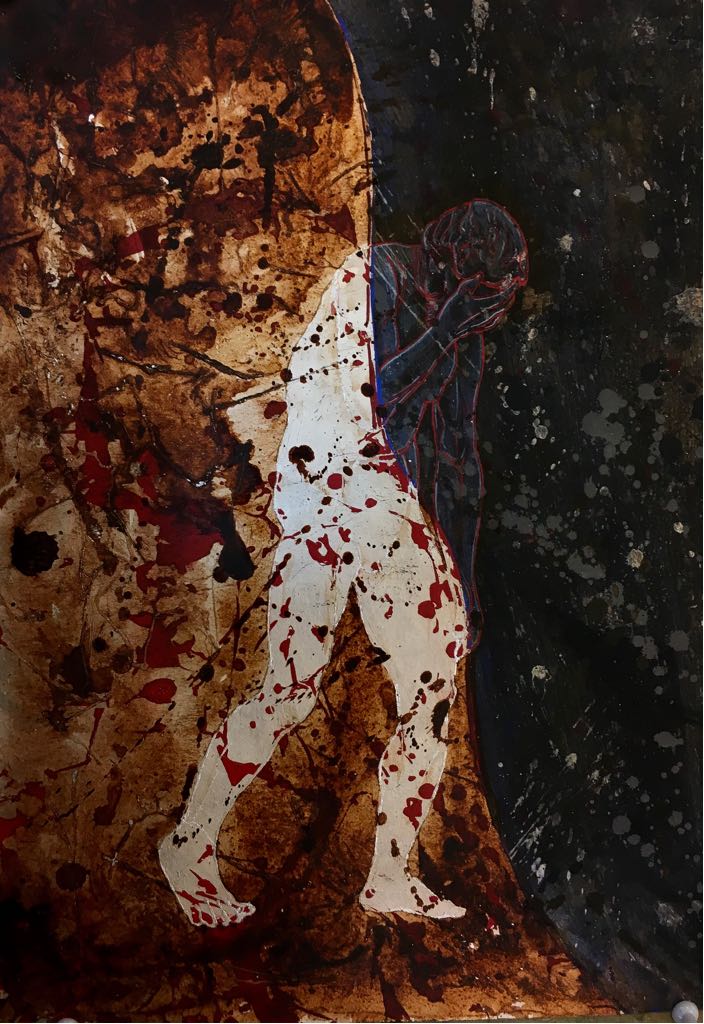

Vineha Sharma’s recent series of works titled Transcriptions borders on notions and beliefs, which could be spoken of as belonging to things of a world not clearly perceived, yet omnipresent. They also refer to the memory that is executed in a certain frame of time. Her works rest upon the seeing of the real and the imagined. She believes that the image resonates beyond the process and the duration of it’s making.

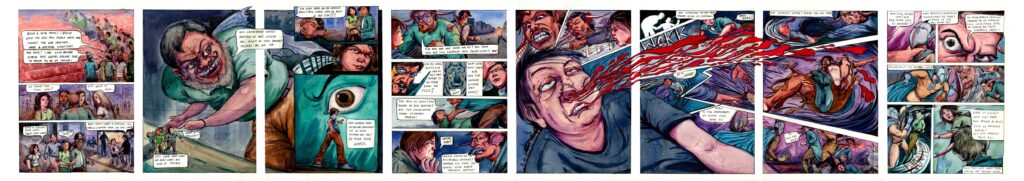

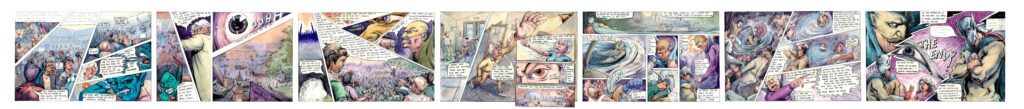

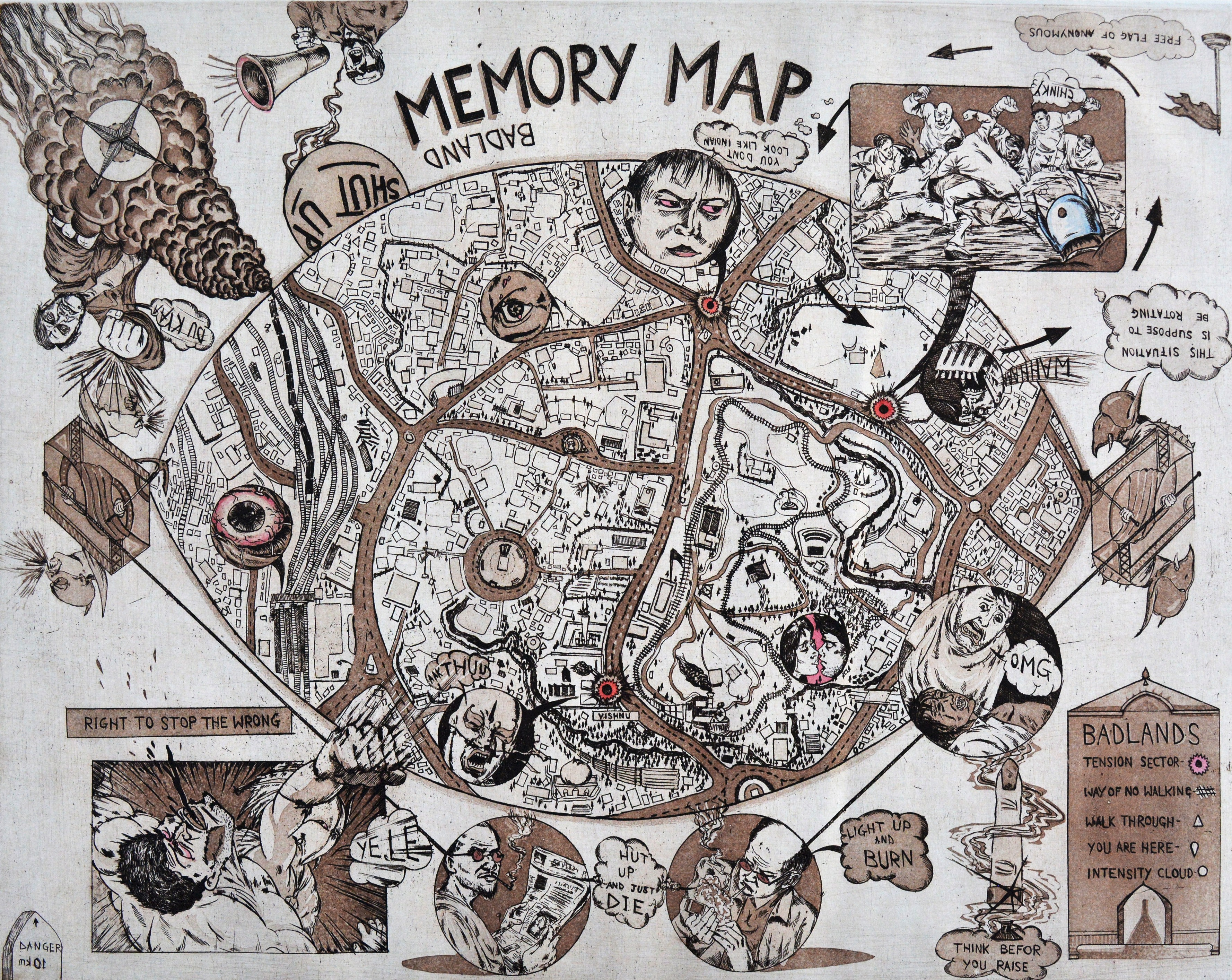

Yogesh Ramkrishna creates a fictional space, ‘Badlands’ in his new series of works titled Tales from the Badlands. The works presented in the form of comic books presents a memory map based on the incidents that he has personally experienced. The profound or horrific events in the works unfolds through the use of dark humour.

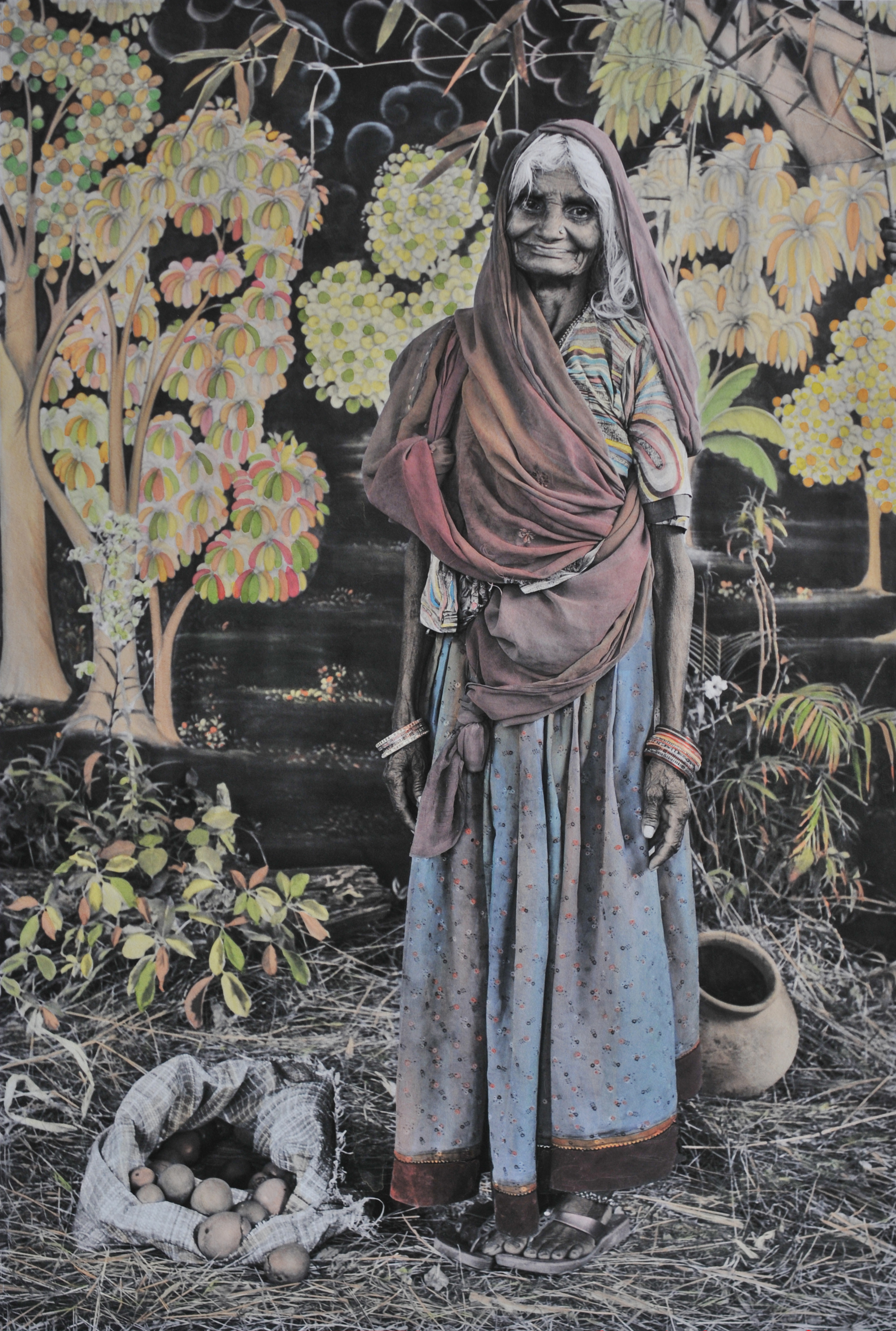

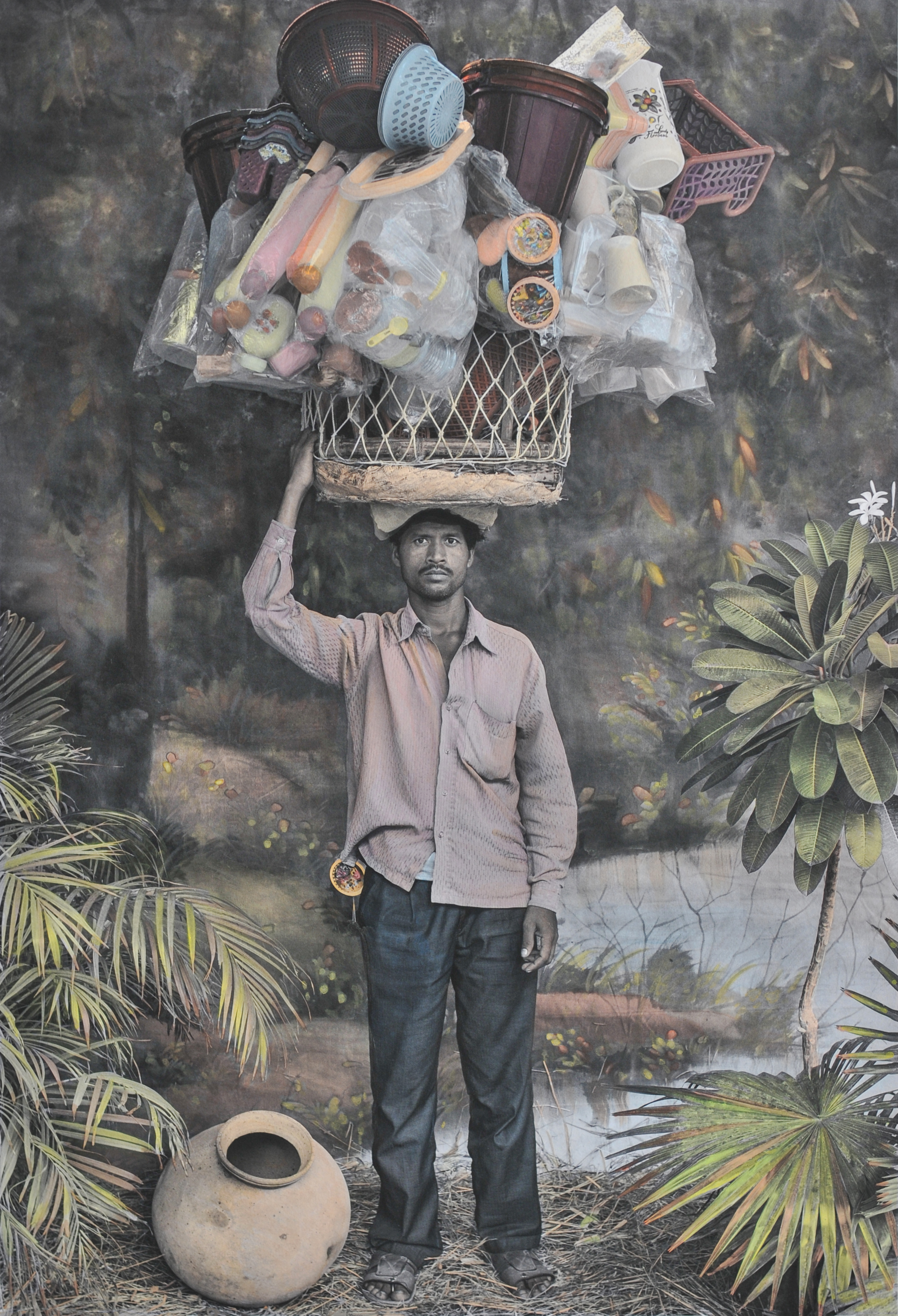

Photographically, Waswo X Waswo’s series Studio in Rajasthandocuments and creates a sense of a world contained in a magical dimension. Ranging from shots of Pheriwallah or the street vendor, a girl holding a field corn, or a mother carrying her child, these photographs draw us into a world of nostalgia. However, at close observation, they also become witty commentaries on the nature of stereotyping, portraiture and representation.

Iranian artist Zahra Yazdani Nia, creates a fictional world that is derived from her immediate surroundings. Her series The Forbidden Lands, depicts the phantasmagoric atmosphere that is symbolic of the Orphic state. Thus, her deep skepticism finds a language in lucid dreaming where she struggles to build a space that is not demarcated by socio-political boundaries. The artist documents her multiple explorations through photographs which are then finally printed using the Cyanotype technique.

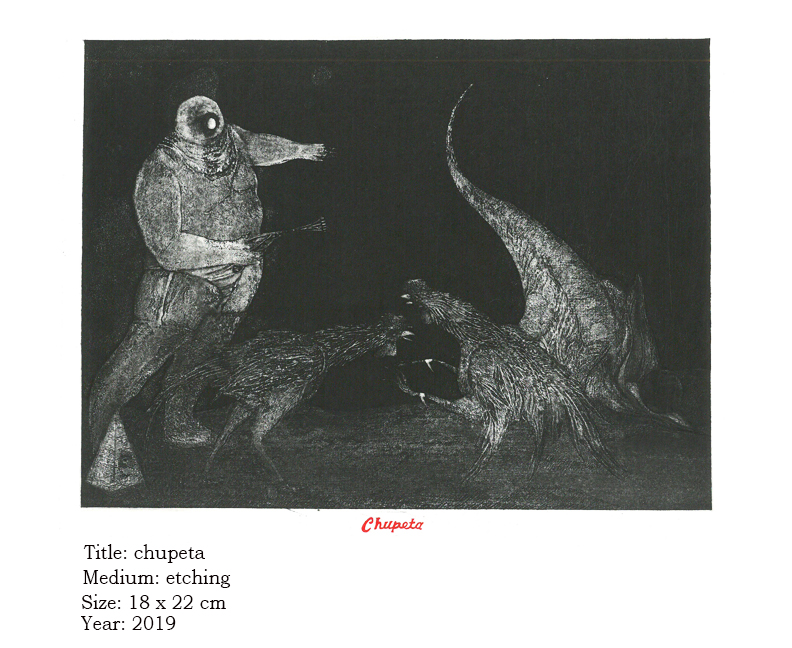

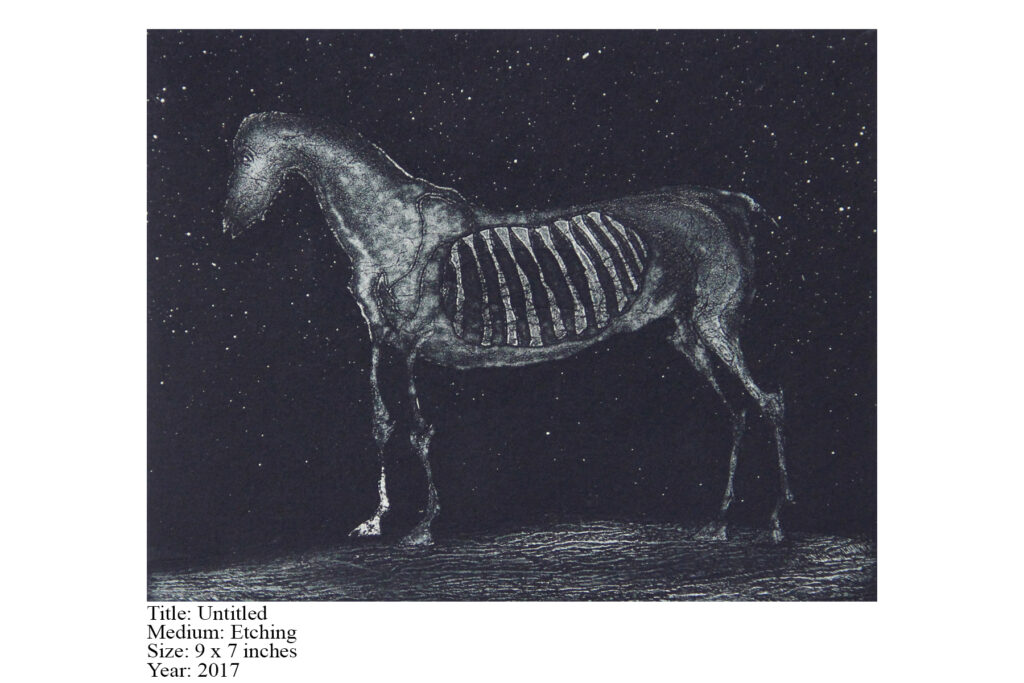

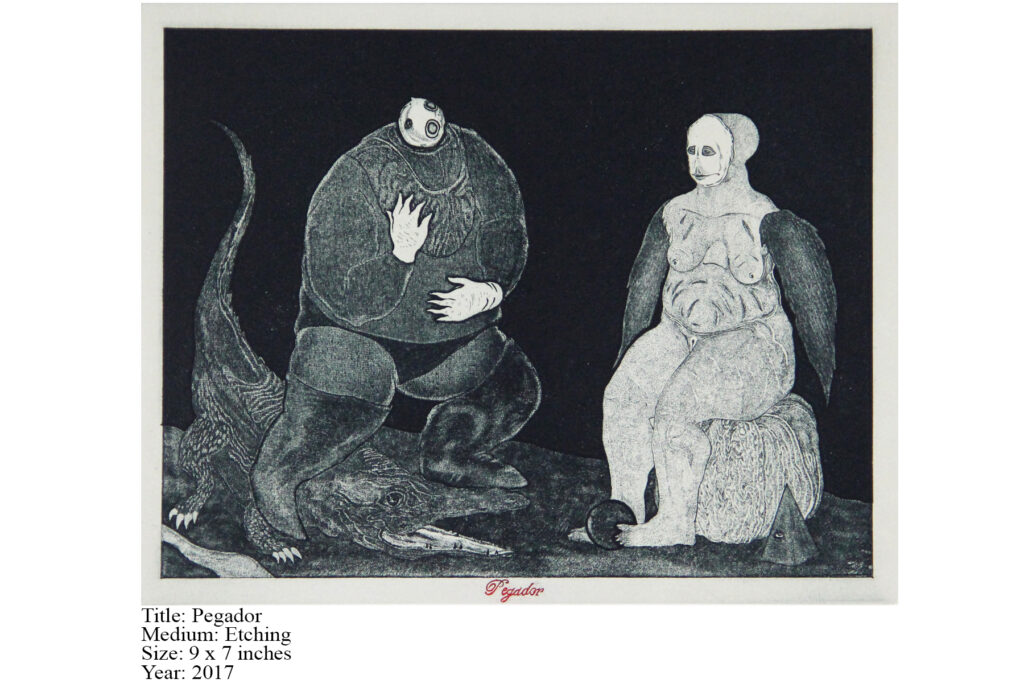

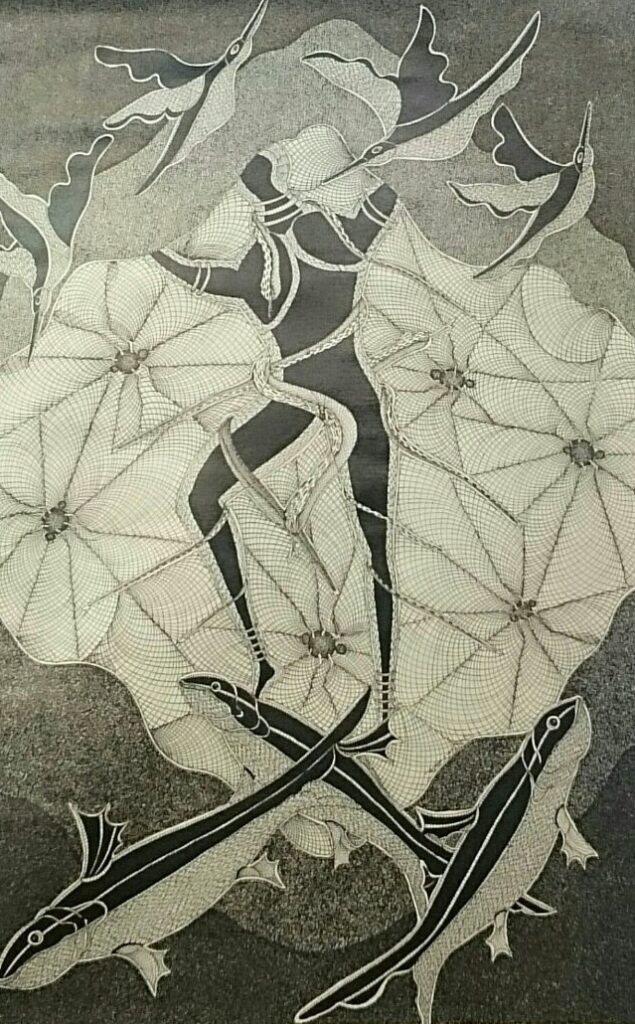

The disillusionment towards the human psyche and failings of the same are depicted in the multi-layered allegorical works by the printmaker Ryan Abreu. His series of prints uses an expression that lies between the genre of dark humour and satire. They employ a somber and grotesque characteristic that attempts to comment on the everyday social traits that derive from a psychological past. The hybrid representations of creatures within a dystopic urban space, becomes a subtle commentary towards the current political conditions. Thus, the works becomes an allegorical representation that enables one to perceive the various notions of the world and the humans inhabiting it.

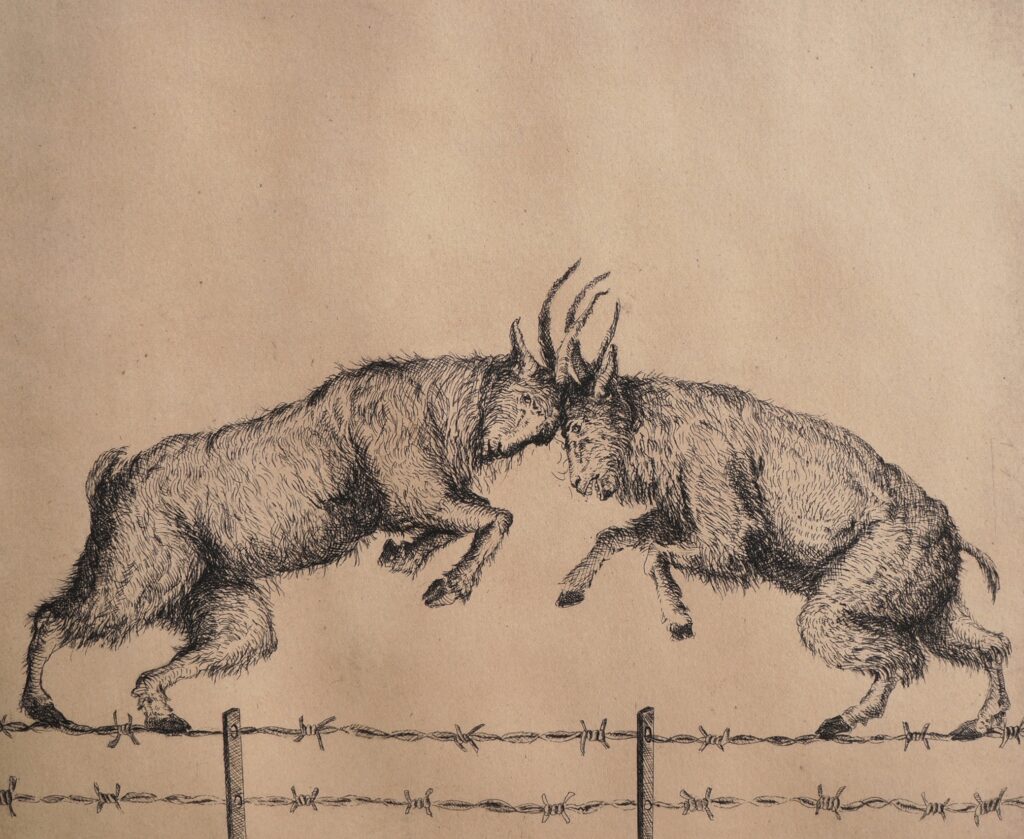

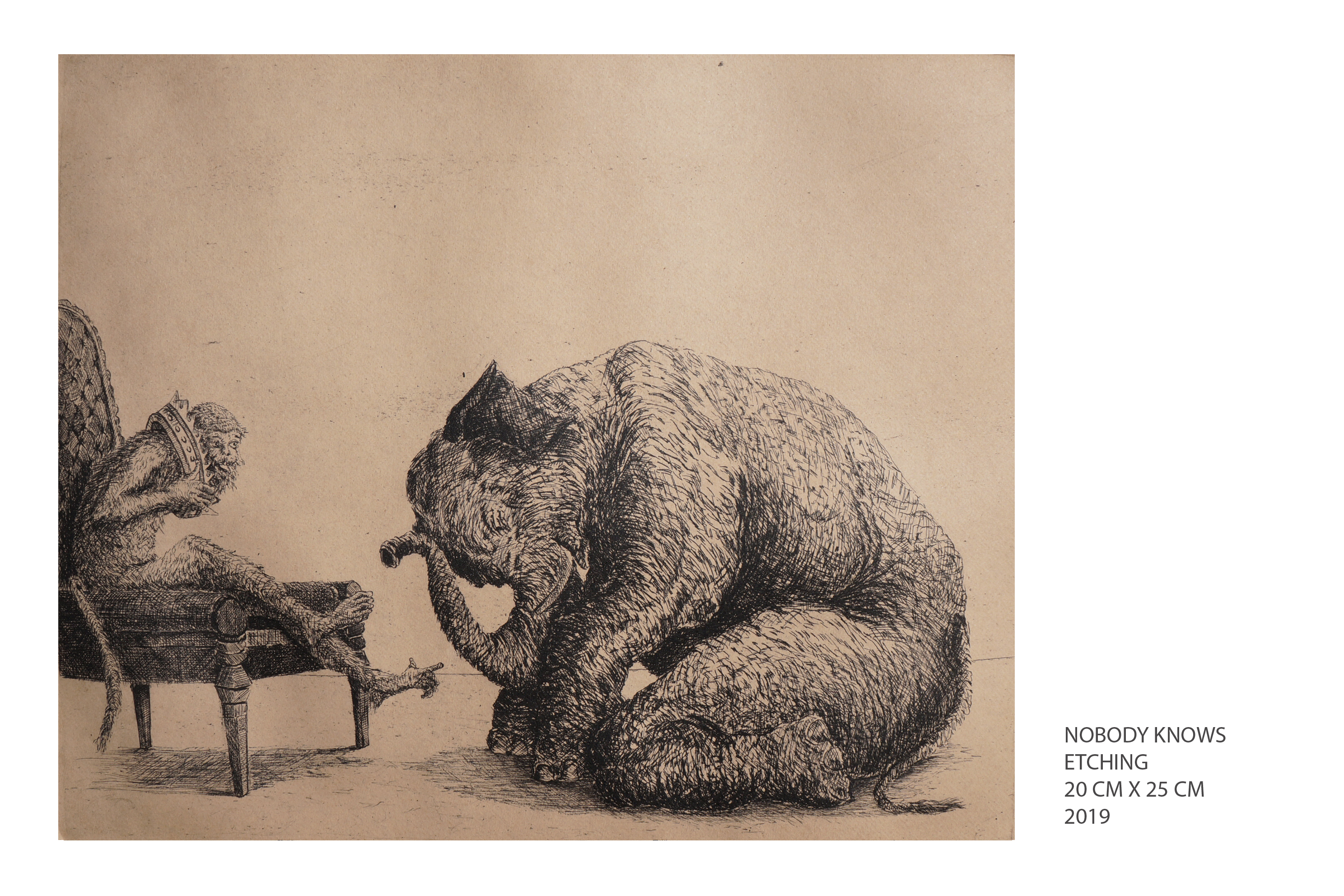

Ketaki Sarpotdar’s print series Nobody Knows, as the title suggests, describes a continuous state of flux and uncertainty. These satirical etchings anthropomorphise various species of animals to question the cynicism, prejudiced identities and perceptions present in the environment. She ponders over the idea of narration and storytelling, through which one form transforms to the next. The personified forms of turtles, donkeys, lions and many others enact the idea of ‘sensible’ human beings. Ketaki’s works are inspired by traditions of fables, folktales, and narratives from around the world.

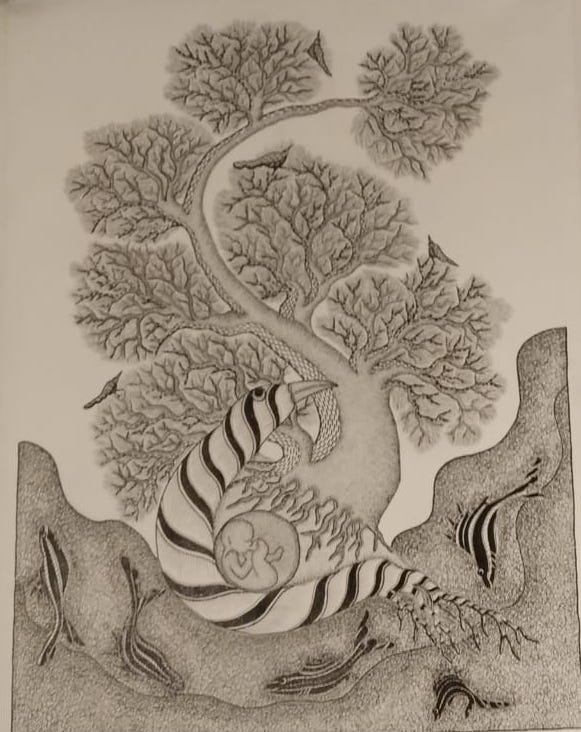

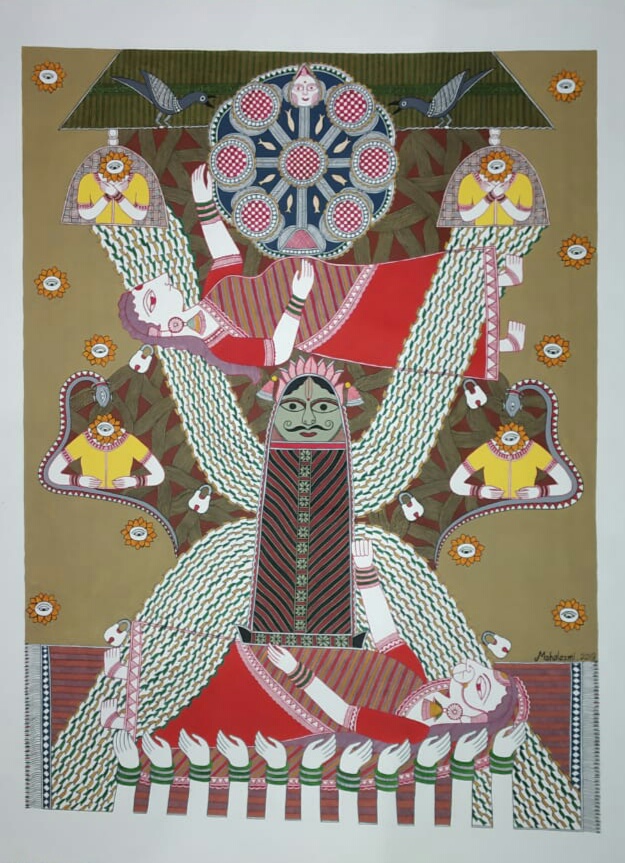

Participating in the exhibition are two indigenous artists using the traditionalGond style from Madhya Pradesh and the Madhubani style from Bihar, to illustrate stories pertaining to communitarian and social concerns. In contrast to the fantastical imaginations of mythological narratives, folk paintings such as these directly capture the immediate milieu that they are part of. The purpose of juxtaposing these works within the larger theme of the show, is to foreground the continuous narrative tropes and analogies that are drawn and made use of by the artists.

Mayank Shyam’s works attempts to depict the various traditions and the stories of the Gond community, such as the story of creation and survival. The birds are symbolic of the open sky that is essential for life, while the trees are symbolic of a place that sustains human life. He invokes Bada Dev, the principal deity who churns the mud and the earth to create mountains, in order to grow trees on it.

Mahalaxmi’swork comments on the status of women in her community. Titled Kobhar, it reveals an interpretation of the nuptial chamber, the auspicious symbol of fertility. Several days before weddings in Mithila, women meet in the Kobhar ghar, where the bride is made to wed the bamboo motif, symbolic of male potency. Mahalaxmi through her work tries to question this tradition and the coded existence that a woman has to share with her husband after marriage. She is thereby seen as someone who only fulfils the pursuit of procreation.

‘Cartography of Narratives’ explores the various forms of narratives that exist today. To illustrate this diversity of narrative methods, the artists draw upon fables, conversations, memories, histories, metaphors, allegories, dreamscapes, among other forms, to confront the notions of appropriation of present-day realities and future possibilities, through still or moving images.

The contrasting experiences between the civilization’s demand for conformity vis-à-vis the influence of a visual language that allows for multiple possibilities was perhaps the starting point for the development of this exhibition. One can therefore encounter hybrid motifs that invariably fuse reality and fantasy to create a collection of signifiers.

By Shalmali Shetty and Rachita Gupta