And The Falchion Passed Through His Neck

GROUP SHOW

Dec 14, 2011 - Jan 15, 2012

- SELECTED WORKS

- CURATORIAL NOTE

- INVITE

- PRESS RELEASE

“And The Falchion Passed Through His Neck”, a group exhibition that includes the new works of artists such as Anjali Bhargava, Chitra Ganesh, Divya Mehta, Hamra Abbas, Samira Abbassy, Sangeeta Sandrasegar and Shweta Bhattad and is curated by Jasmine Wahi. This exhibition, inspired by the work of Gentileschi, is a diverse representation of the reinterpretation of strong feminist icons through the use of historical and religious iconography to convey female empowerment in contemporary society. The distinctive use of ‘promiscuous imagery’ and violence symbolize a positive rebellion against the suppression of women as sexually and politically empowered beings. Each work in the show is dually inspired by a female heroine and the artist herself as a strong female figure within the context of her own society. Be it a goddess, biblical character, or historically significant being- each subject disregards the misogynistic constraints prescribed for women.

CURATORIAL NOTE

AND THE FALCHION PASSED THROUGH HIS NECK…

Curated by Jasmine Wahi

Anjali Bhargava | Chitra Ganesh | Divya Mehra | Samira Abbassy |

Shweta Bhattad | Sangeeta Sandrasegar | Hamra Abbas

When I was still in the nascent stages of my art history love affair, I encountered Artemisia Gentileschi, an Italian artist from the early seventeenth century who inspired me not only as a student hungering for controversy in art, but also as a budding women’s activist with the fire of Linda Nochlin’s ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists’ (1971) burning in my heart. These sources strengthened my belief that Sexual, Intellectual, Religious, Professional, Creative, and Personal freedoms are just a few basic rights that all women are entitled to. Though there are still many areas where women are denied these basic rights, we have come far from where we were several centuries before. The matriarchs of art have brought us where we are today, and drawing from their strength, today’s creative and empowered women are able to continue pushing forward for universal practice of freedoms for all. This exhibition is an acknowledgement of progression from the social confines of the past and a look at the ‘rebellious’ imagery that continues to push us forward. It is a reinterpretation of the historical, religious and social views of women. Each work approaches overtly sexually suggestive or pugnacious imagery as a means to convey female empowerment in contemporary society. The distinctive use of ‘promiscuous’ symbolism and violence, serves as a positive rebellion against the suppression of women as sexually and politically empowered beings.

Gentileschi’s ‘Judith Beheading Holofernes,’ which she painted in the twilight of her youth, circa 1612, has served as the springboard for this exhibition. In the years and centuries following the painting’s completion, it has been heralded as a symbol of feminism and an aggressive step towards the conquering of misogyny. The work serves as an illustration of the Old Testament parable from the Book of Judith. In the story, Judith, the beautiful Jewish widow seduces Holofernes, a tyrannical Assyrian General sent to pillage and plunder her country. Allowed to enter the chamber of Holofernes because of her legendary beauty, Judith proceeds to seduce the General with her charm and an array of libations. When sufficiently stupefied, the invader falls asleep; after which Judith violently decapitates him with a falchion (sword). The story itself is aptly summed up in just two lines from the chapter: “Her sandals ravished his eyes, her beauty took his mind prisoner, and the falchion passed through his neck” (Old Testament: Book of Judith 16:9). It is a classic tale of heroism and at its core, a mythological, if not historical trophy in women’s history. What makes this work particularly unique is the autobiographical element. Gentileschi painted herself in Judith’s stead, symbolically confronting her rapist, Agostino Tassi, who is depicted as Holofernes. Chitra Ganesh’s self portrait as Rani of Jhansi (2005), the woman warrior of India who led a siege against the British, is another exemplification of a ‘hurrah!’ moment in women’s history. Although she is slain in this image, I see it not as a tragic print, but as an empowering instance of dynamic perseverance.

Samira Abbassy’s ‘Infidelity’ (2009), is another pseudo-self-portrait that takes a page from Gentileschi’s justifiably vengeful painting. In Abbassy’s image, an unidentified, yet remarkably Holofernes-like figure’s head rests haphazardly on the floor. Abbassy’s aesthetic draws from ancestral techniques employed by miniaturists. She rejects conventional perspectives of foreground and background and instead ranks the prominence and power of each figure by size; the bloodied figure to the right can most likely be assumed to be not only the executioner, but also the victor and heroine of the image, similar to the figure of Judith as seen in medieval imagery. The employment of size variations is subtle fodder indicating the dominance of the female figure.

For better or for worse, the reception of Gentileschi’s work has not been all positive, particularly in the early seventeenth century. From its inception, her painting has been the focus of both admiration and controversy. Her rendition of the tale depicts the beheading in action- the knife plunging through the neck of her attacker. The mix of violence (masculine) and grace or beauty (feminine) has been interpreted by both historical and contemporary scholars as contradictory; though actually, it is no secret that women are capable and culpable of being both graceful and violent, as are all people. According to Nolchin’s 1971 essay, the gauge of what is feminine and masculine, particularly in the artistic arena, is unsurprisingly a societal infliction that derives from a predominantly male prescription of how social roles should be played out.

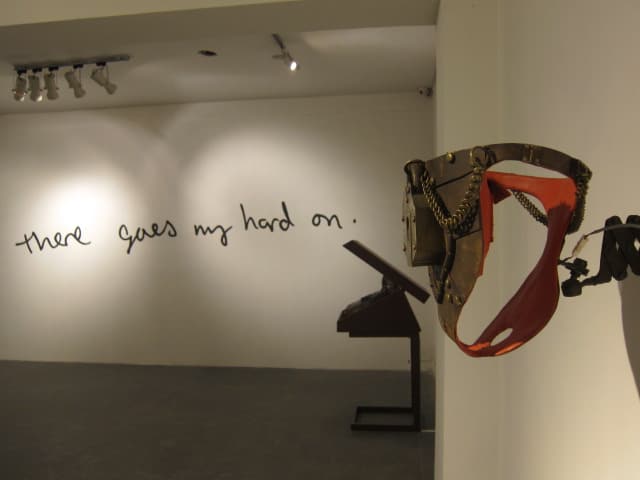

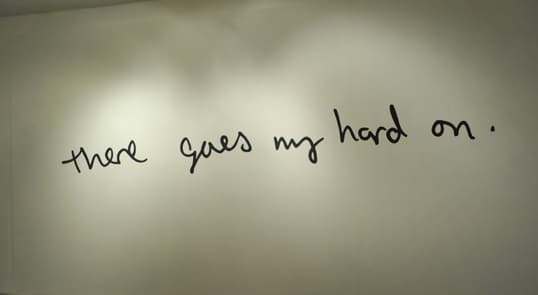

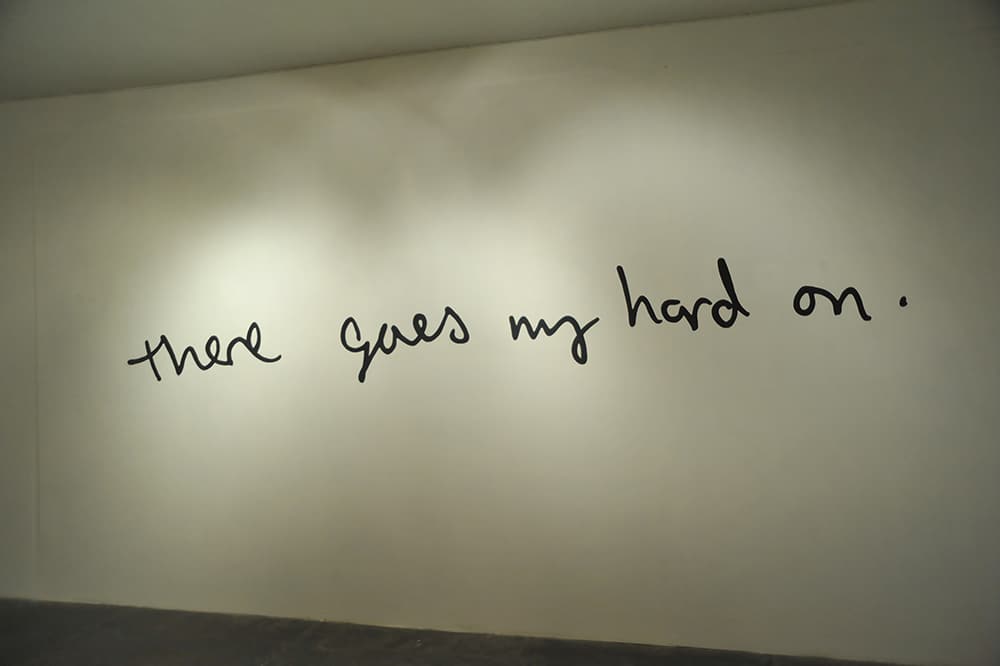

With respect to women, as one can see through a wide range of diverse cultural outlets, there has been an overvaluation of chastity, virginity, demureness, and subdued behavior. Freedom of sexual expression, aggression, intelligence, and creativity have been stifled and smothered. Women who are overt and expressive have been (and are often today) frowned upon, if not shunned and rejected. Divya Mehra’s video piece ‘PANTS’ (2006) is the only piece in the show that exemplifies the not-so-long-ago suppression of women as independent beings. Although it is darkly humorous in execution, the piece explores the negative perception and fear borne by a woman acting like a man (wearing pants, drinking, venturing out alone). Of course the video is not literally about her choice of pants over traditional attire, but more about the audacity of breaking with tradition and femininity. Perhaps her husband would have preferred his companion to don a chastity belt to which he held the key…

The chastity belt was not a practical means for population control or to maintain ‘purity,’ which is itself an arbitrary concept. In fact, this stylish and popular contraption was merely a way to control a woman’s physical freedoms. Shweta Bhattad’s multimedia chastity belts, particularly ‘Releasing Suppressed Emotions 1’, utilize the shape of the vaginal prison; however, subvert the original intention of the object into a platform for personal expression and conquering that which suppresses us, through our own inner strength. Though Bhattad does not present the chastity belts as veritable female torture devices, there is no denying that the work very deliberately creates a female-specific dialog; addressing the complexities of persona, and the woman’s ability to be both violent and chaste, pious and evil. She derives this from Hindu mythology in ‘Venus Fly Trap II’. The prevalence of mixed-gender attributes in the divine is quite common, not only in Hinduism, but also among several other religious factions, such as the Greco-Roman religions, Christianity, and Judaism to name just a few. The glaringly obvious examples being Judith, Athena, and Kali- as depicted in both Samira Abbassy’s painting ‘Kali’s Mirror’ and Sangeeta Sandrasegar’s circumambulatory work (2011). Abbassy’s ovular work again reverts back to the depiction of a violent and vengeful wrath. The braided youth to the left of the guillotined figure holds up a mirror, indicating either self-admiration or self-reflection. Sandrasegar’s work is also a tribute to Kali and Durga, depicted through the multiple arms of the goddess. This work not only pays homage to the goddess, but to all women created in her image. This correlation with the goddess extends further into the realm of eroticism and sensuality.

Anjali Bhargava’s ‘Suffocation Series’ (2009) also alludes to the goddess, as an homage to the sensuality and perfection of the divine. Both suggestive and self-reflective, the work explores the erotic thread that pervades Hinduism in both scripture and art, and how that which is divine translates into reality. Borrowing inspiration from Oscar Wilde’s ‘In the Gold Room’, Bhargava waxes on the implication of rouged lips. She says, “The etymology of the word red is connected to the Sanskrit word “Rudhira” which means blood, bloody or red. But it wasn’t just Kali who was portrayed with red lips. Saraswati, Lakshmi and any number of the more beatific goddesses bear sweetly smiling red lips.” Each image can be dually interpreted either as a portrayal of divinity or a seductive invitation. The last image in the series, ‘Contented’, is either a display of post-coital ecstasy or (for those of us who endured many years of Greek and Roman art history surveys) or the archaic smile of the divine. Bhargava’s suggestion is that the goddess, as one can also see on ancient Karmic sculptures in Kajaraho and elsewhere, and consequently her human counterpart are flagrantly sexual beings.

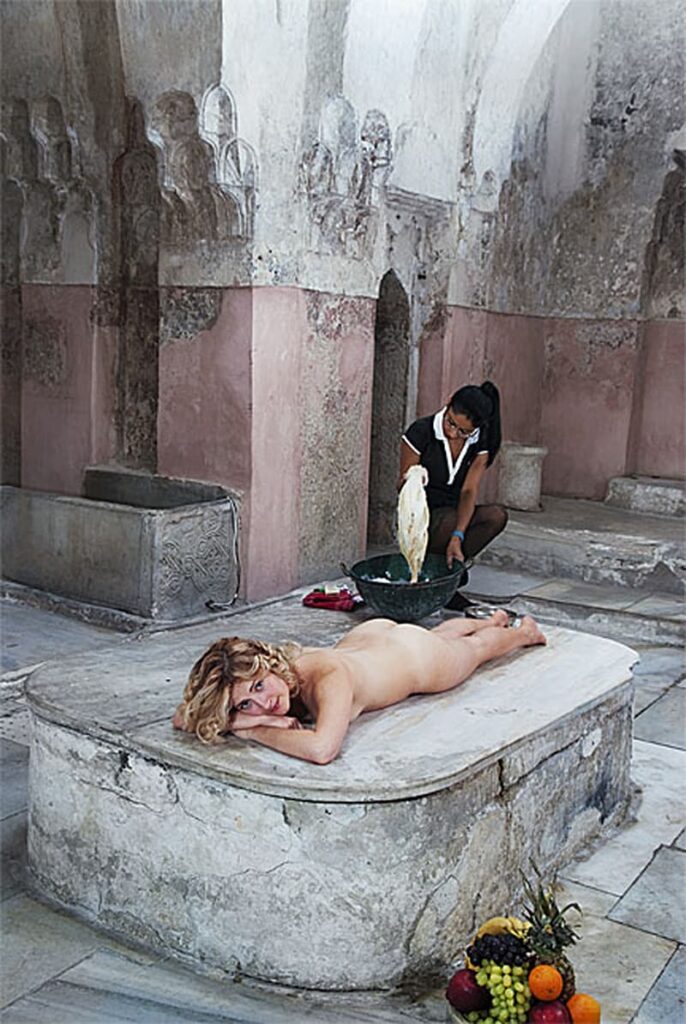

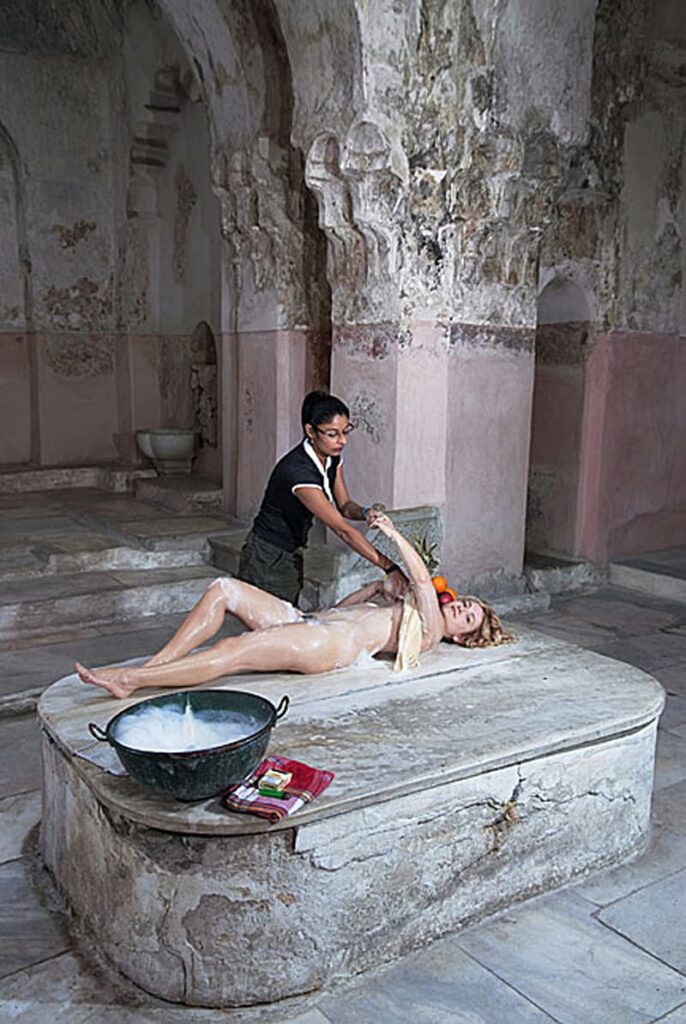

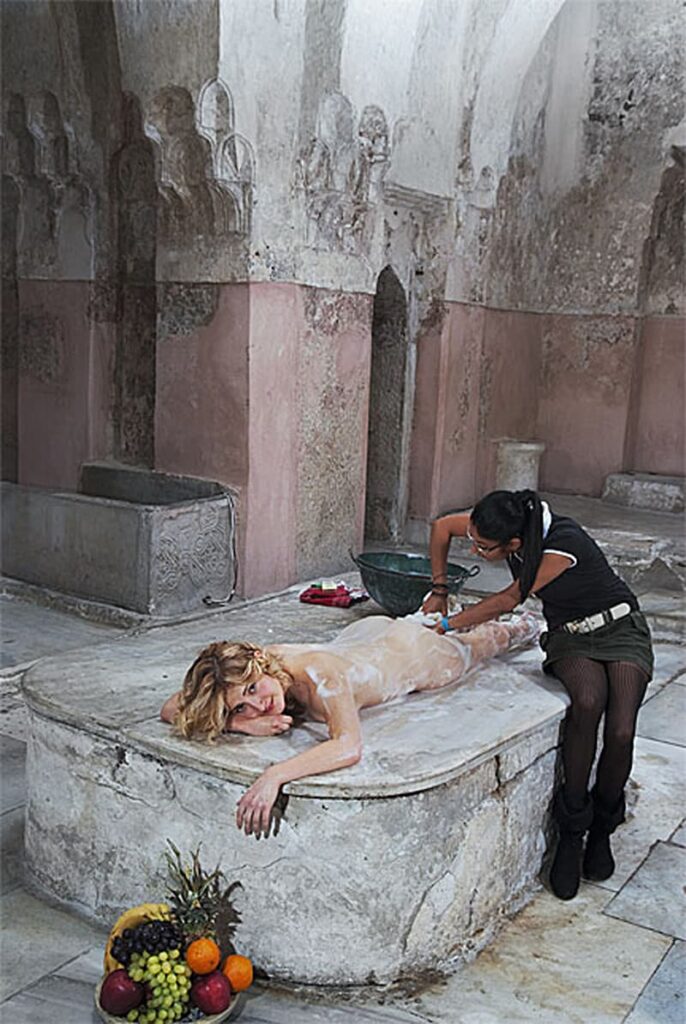

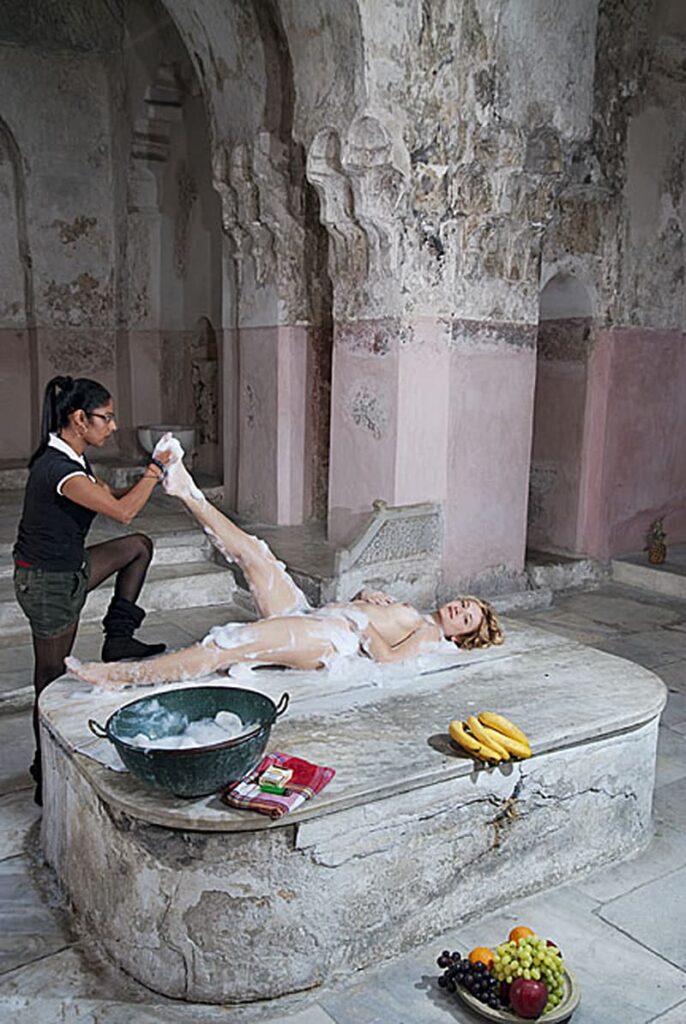

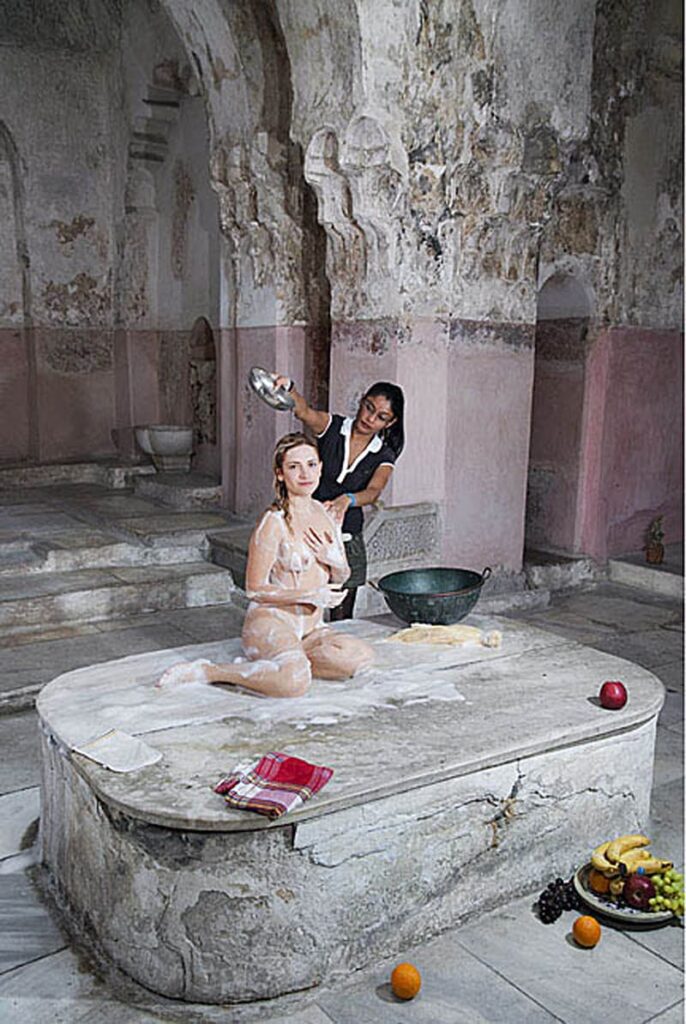

This feminist rebellion is expressed through blatant displays of eroticism reinforced in And the falchion passed through his neck… with Samira Abbassy’s ‘Mother of Silences, Seer of the Unseen’- in which there is clear female dominance, and perhaps an allusion to sexual sadism. Hamra Abbass’ series of nine performance photographs, ‘Paradise Bath’ (2009) also alludes to power play through the act of washing or cleansing a woman in the ritual of bathing. Her original performance was intended to explore issues of race, power, and memory; however, there are also elements of homoeroticism in this undeniably titillating series of images. The performative element in the piece versus the conventionally private practice of bathing illustrates that lack of shame or concern for exposing and manipulating the body. The openness and deliberate sharing of the bathing process illustrates more than a disregard, a defiance towards suppressing the sexual elements of the act.

CURATOR BIO

Jasmine Wahi Contemporary is a multi-division company that primarily works in Curation and Art Advisory. Jasmine Wahi, a graduate of New York University, is a seasoned curator, critic, and advisor. After exploring both the commercial and non-profit sectors of the art world, Ms. Wahi opened up her own consultancy which focused primarily on cultivating emerging artists. Since it first opened, Jasmine Wahi Contemporary has grown beyond an advisory service to include curatorial projects and non-profit endeavors.

In 2010 Ms. Wahi Co-Founded Project For Empty Space (www.projectforemptyspace.com), a non-profit arts organization in New York City that is dedicated to bringing Contemporary art to a multitude of communities through the utilization of abandoned and unusual urban spaces. In 2011 Project For Empty Space expanded it’s programming to other parts of the world including Bogota Columbia. Project For Empty Space is supported by Jasmine Wahi Contemporary.