The World Awaits You Like A Garden

GROUP SHOW

Apr 26, 2022 - Jun 30, 2022

- SELECTED WORKS

- CURATORIAL NOTE

- PRESS RELEASE

The World Awaits You Like A Garden

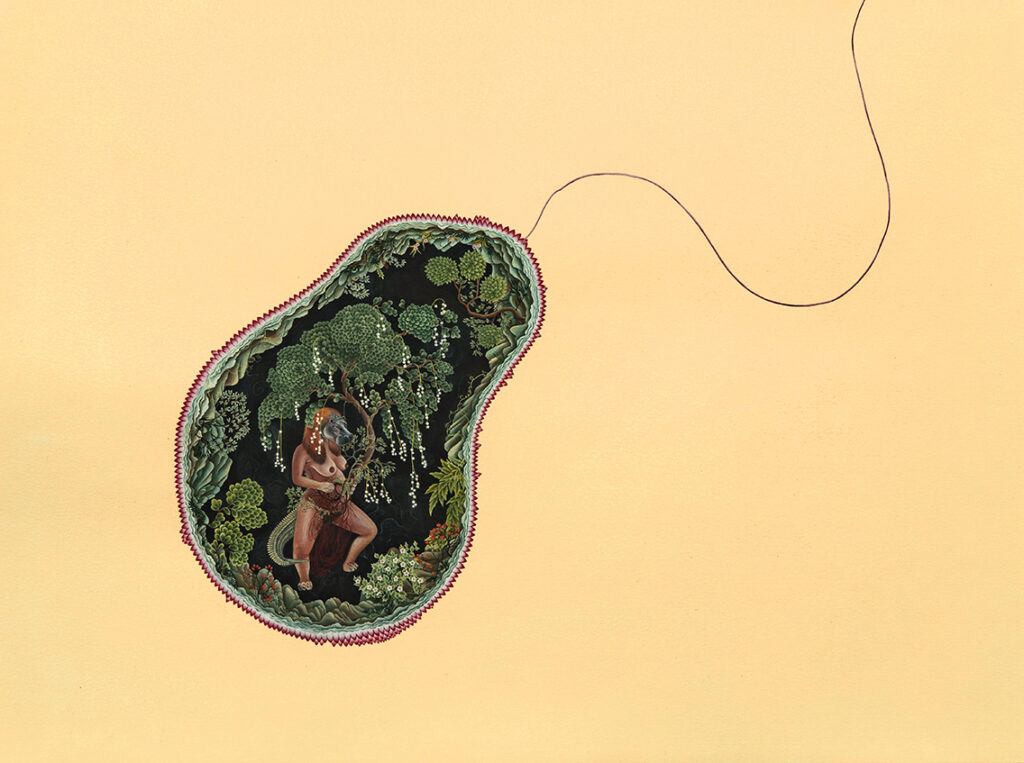

“Step out from the cave to encounter the world like a garden, the eagle and the snake urge Zarathustra. Or so Friedrich Nietzsche writes in Thus Spoke Zarathustra. For the German philosopher, the garden is a geophilic site of sensorial engagement, a space where the wind carries heavy fragrances and songbirds teach us to sing. Imagined in the last decade of the nineteenth century, Nietzsche’s world as a garden is not the human-earth or the Menschen-Erde, a putrefying cave of anthropogenic climate change, but an uncanny landscape that can only be occupied through an ethics of care. The form of practice that emerges therein is heuristically arranged with the world rather than against it. Let us step into Nietzsche’s garden.”

– Excerpt from the curatorial note by Sugata Ray

CURATORIAL NOTE

The World Awaits You Like A Garden

Step out from the cave to encounter the world like a garden, the eagle and the snake urge Zarathustra. Or so Friedrich Nietzsche writes in Thus Spoke Zarathustra. For the German philosopher, the garden is a geophilic site of sensorial engagement, a space where the wind carries heavy fragrances and songbirds teach us to sing. Imagined in the last decade of the nineteenth century, Nietzsche’s world as a garden is not the human-earth or the Menschen-Erde, a putrefying cave of anthropogenic climate change, but an uncanny landscape that can only be occupied through an ethics of care. The form of practice that emerges therein is heuristically arranged with the world rather than against it.

Into The Garden

Let us step into Nietzsche’s garden. In New Delhi, the world’s most polluted capital city according to the World Air Quality Index, this garden might as well be a chimeric mirage today. Nonetheless, the longue durée history of landscaping reaches back to the fourteenth century. Echoing the implorations of the eagle and the snake in Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra, here is the poet Mutahhar of Kara describing the Hauz Khas madrasa and garden built by the emperor Firuz Shah Tughluq in 1352:

The courtyard was soul-animating, and its expanse was life-giving. Its dust was musk-scented, and its fragrance possessed the odour of amber. There was verdure everywhere, and hyacinths, basils, roses, and tulips were blooming and were beautifully arranged so far as the human eye could reach. […] Nightingales, so to say, were singing their melodious songs everywhere.

In the sixteenth century, the “life-giving” gardens in and around Delhi would become ecopolitical sites of spectacular pageantry, revelry, and leisure under Mughal rule. In the eighteenth century, Delhi’s garden would be recalibrated once again, this time through colonial modernity’s spectatorial regimes of seeing and ordering the natural world.

The spectre of Delhi’s many gardens may haunt us as we step into Nietzsche’s garden, not through a fetishized romanticization of Edenic ecoscapes of the past but through vestiges erased by the stranglehold of smog and concrete. But life—contaminated, mutated, radioactive, hybrid—still perseveres in the shadow of the Anthropocene.

The Garden is Planetarity by Another Name

In Thus Spoke Zarathustra, the eagle gathers yellow and red berries, grapes, rose-apples, fragrant herbs, and pine-cones for the convalescing mystic. Upon waking from his seven-day stupor, Zarathustra breathes in the aroma of the rose-apples amassed by the eagle and then asks the animals to chatter (schwätzen). The intersubjective arena that is thereby enunciated undoubtedly shapes an ecological continuum at odds with our current anthropocentric definitions of both nature and culture. For the arena for interaction between species is limited under ordinary circumstances just as chatter, or animal speech, is indistinct to our ears.

Is Nietzsche’s world as a garden then planetarity by another name? Indeed, as early as 2003, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak had proposed that alterity would remain underived from us if we imagine ourselves as planetary subjects rather than global agents. For the feminist critic, the global was indelibly linked to the alienation of capitalism. Can we step into the garden, not as a site of ecotechnological control, domination, and resource extraction, but as an entangled space caught up in processual flows where subject-object binaries become obscure? Can we learn from the songbirds, those nightingales in Hauz Khas, how to be planetary subjects despite the ghostly amnesia that now haunts the topography of Anthropocene Delhi? Can we envisage a practice of living that foregrounds a contingent correlation of equivalence with nonhuman worlds?

An engagement with phyto-worlds solely through a modernist paradigm that focuses on human mediations in ordering, managing, and mastering the ecologies of plants, flowers, fruits, roots, and seeds runs the risk of reiterating, yet again, our species-level objectification of the environment. In contrast, the act of dwelling or being in the garden as a planetary oikos offers a framework to envisage a more capacious relationship between human and nonhuman worlds. In turn, the resiliency of place-making as repair enacts inventive play that forms a liminal threshold of transformative aesthetics based on sensuous interactions between plants and humans. As the eagle and the snake remind Zarathustra (and us):

Step out from your cave: the world awaits you like a garden. The wind is playing with heavy fragrances that would come to you; and all streams would like to follow you.

By Sugata Ray