The Exodus of Eternal Wanderers

Jan 17, 2020 - Feb 28, 2020

- SELECTED WORKS

- CURATORIAL NOTE

- INVITE

- PRESS RELEASE

- DOWNLOAD CATALOGUE

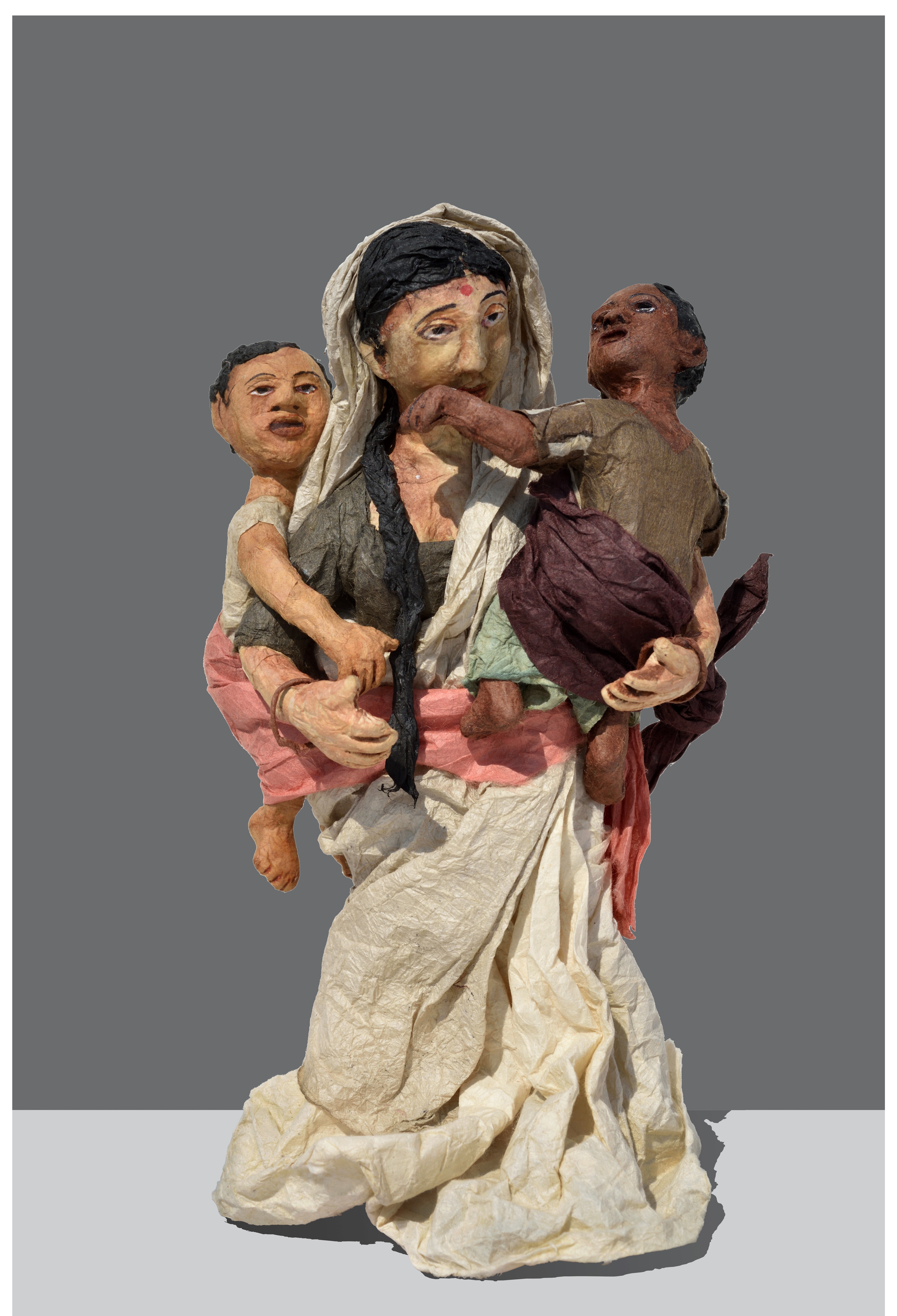

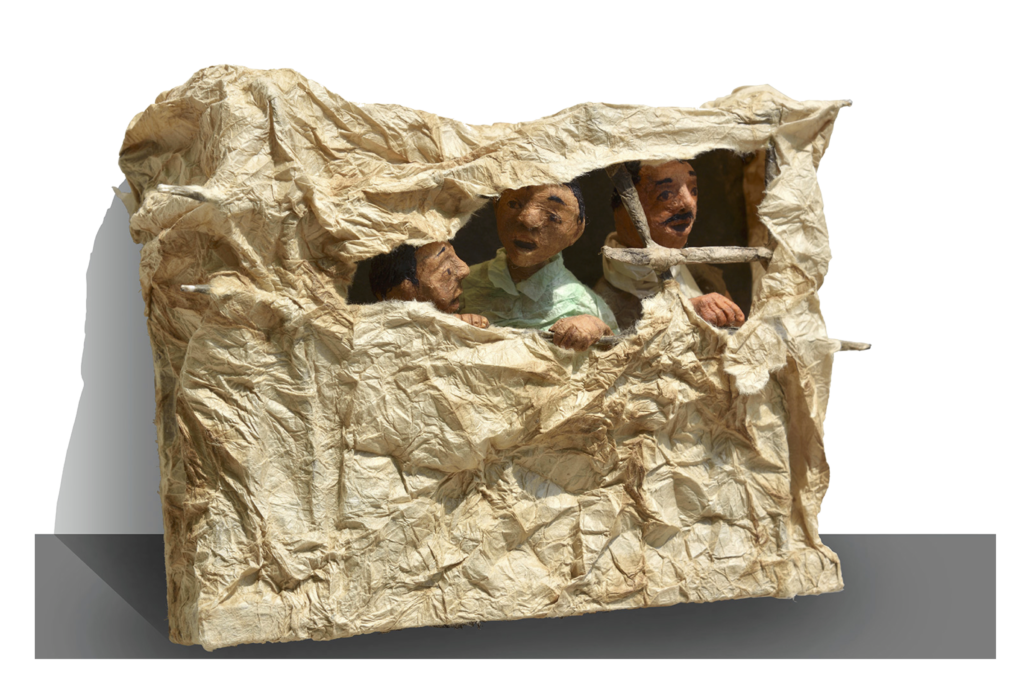

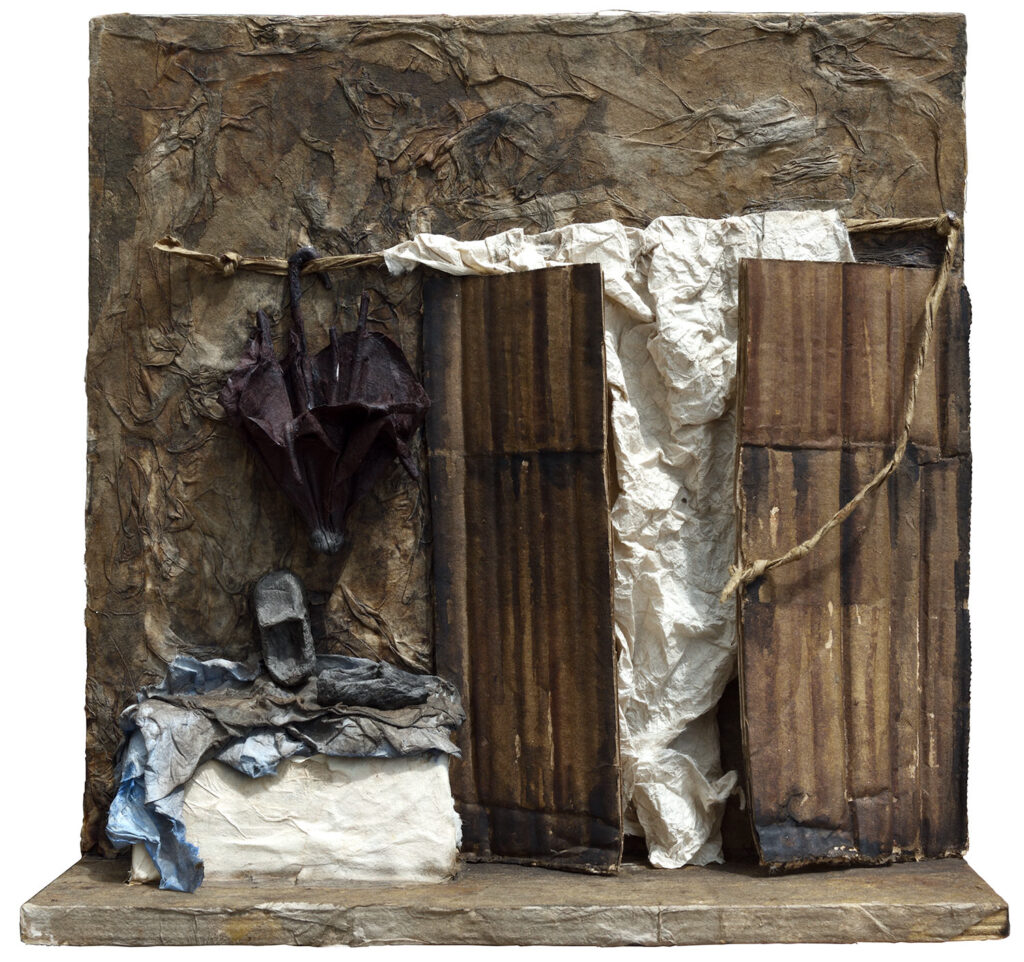

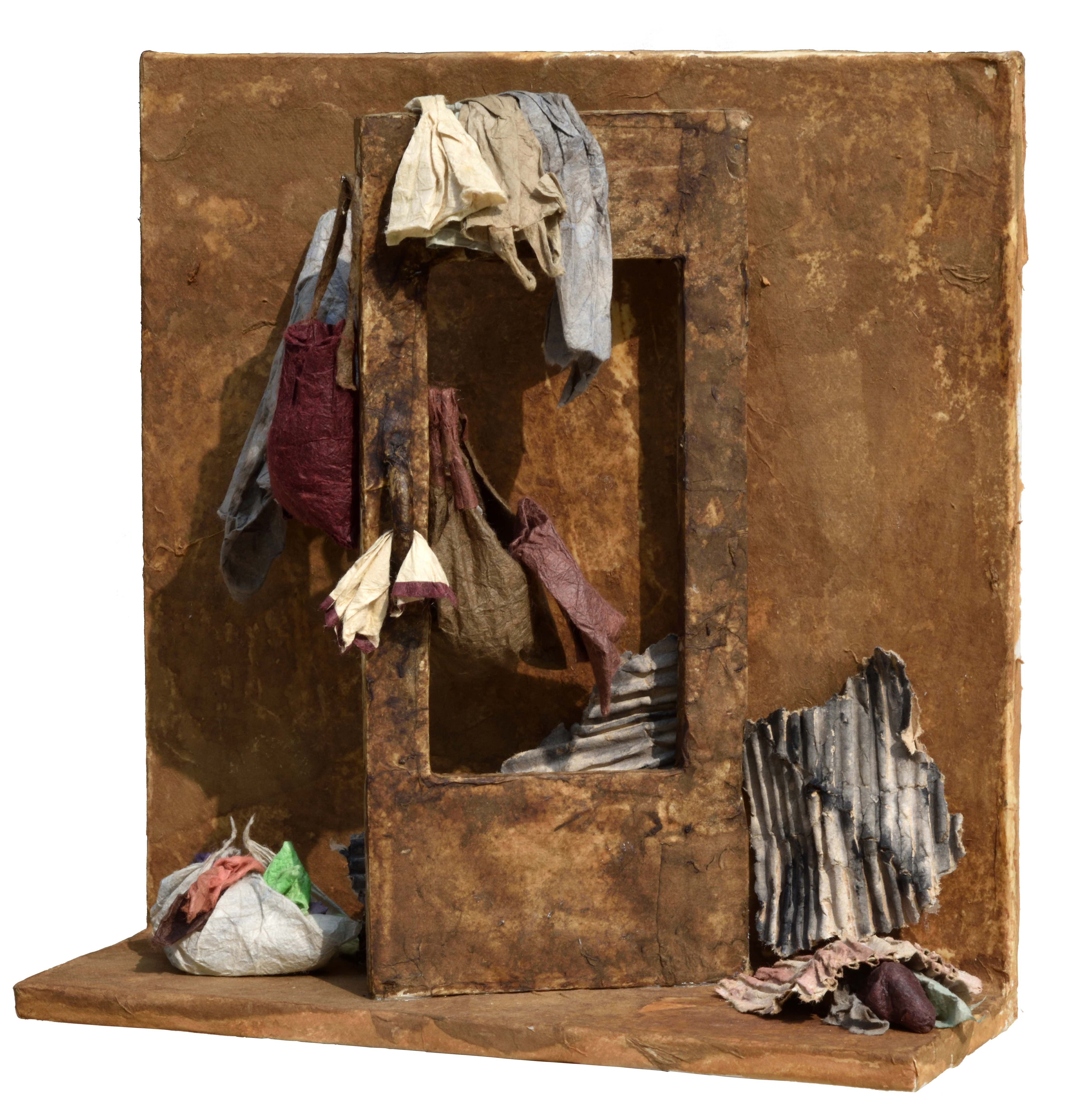

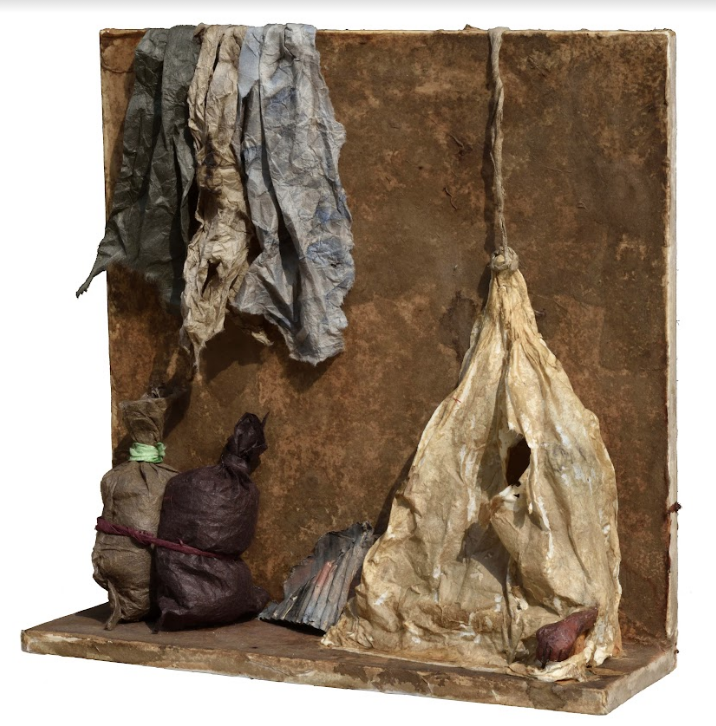

In her latest exhibition, Baroda based artist Sudipta Das interrogates the realities of climate change and appeals to humanity about its most important outcomes, human migration. Through her paper sculptures, Sudipta represents the slow violence of ongoing disasters specific to her hometown Silchar, Assam and the precarious pasts as well as the futures of its victims. Nonetheless, the miniaturized representation of the human exodus, repeating in an endless loop reckons the universal emergency of human displacement now more than at any point in human history. Her sculptures of wandering figure in search for self-respect within a larger collective brings to mind Hannah Arendt’s observation that the refugees “fight like madmen for private existences with individual destinies.” Sudipta’s powerfully raw and vivid works unpack the horrors of a continuous displacement which gets repeated year after year. Some return to the devastated homes while many wander in search of newer destinies. Her immersive installations of these miniaturized human figures and sculptures are influenced by personal experiences, archival materials and family histories. She uses these to conjure an eternal journey in search of a home, depict the painful life in exile, and introduce an existential dilemma of unparalleled scale. The underlying message stretches on to the global scale of displacement especially in the context of climate change. Sudipta reminds us that these displaced wanderers and their eternal exodus are not a new phenomenon. Their struggle has a long history and this displacement due to climate change is compounded by many other contemporary humanitarian crises will lead to more people being on the move. In this journey they are rendered stateless, they are stripped of basic rights as legal rights are only bestowed upon citizens of a nation-state and their silent precarious existence constantly seek hospitality and justice. These small sculptures appeal to the contemporary politico-legal frameworks in futility, despite being only met with hostility and indifference from everywhere. Sudipta’s attempt to expose this vulnerable world of the climate refugees to garner emotional support may appear quixotic. But when communities are destabilized and waves of bodies set in exodus, can we only rely only on the impartial callousness of legal frameworks? She foregrounds the necessity of new political ideas, collective imaginations, and compelling narratives.

CURATORIAL NOTE

In her latest exhibition, Baroda based artist Sudipta Das interrogates the realities of climate change and appeals to humanity about its most important outcomes, human migration. Through her paper sculptures, Sudipta represents the slow violence of ongoing disasters specific to her hometown Silchar, Assam and the precarious pasts as well as the futures of its victims. Nonetheless, the miniaturized representation of the human exodus, repeating in an endless loop reckons the universal emergency of human displacement now more than at any point in human history. Her sculptures of wandering figure in search for self-respect within a larger collective brings to mind Hannah Arendt’s observation that the refugees “fight like madmen for private existences with individual destinies.” Sudipta’s powerfully raw and vivid works unpack the horrors of a continuous displacement which gets repeated year after year. Some return to the devastated homes while many wander in search of newer destinies. Her immersive installations of these miniaturized human figures and sculptures are influenced by personal experiences, archival materials and family histories. She uses these to conjure an eternal journey in search of a home, depict the painful life in exile, and introduce an existential dilemma of unparalleled scale. The underlying message stretches on to the global scale of displacement especially in the context of climate change. Sudipta reminds us that these displaced wanderers and their eternal exodus are not a new phenomenon. Their struggle has a long history and this displacement due to climate change is compounded by many other contemporary humanitarian crises will lead to more people being on the move. In this journey they are rendered stateless, they are stripped of basic rights as legal rights are only bestowed upon citizens of a nation-state and their silent precarious existence constantly seek hospitality and justice. These small sculptures appeal to the contemporary politico-legal frameworks in futility, despite being only met with hostility and indifference from everywhere. Sudipta’s attempt to expose this vulnerable world of the climate refugees to garner emotional support may appear quixotic. But when communities are destabilized and waves of bodies set in exodus, can we only rely only on the impartial callousness of legal frameworks? She foregrounds the necessity of new political ideas, collective imaginations, and compelling narratives.

Many decades ago when Arendt wrote We Refugees she observed that the conventional definition of a refugee is a person driven to seek refuge because of some act committed or some political opinion held. But she noticed that most of the Jews who fled Nazi Germany did not possess a strong political opinion and many of them detested the word refugee. But in this exiled subjectivity Arendt located the vanguard as they have already experienced and recognized what to others has only become obvious today. Arendt has then rightly highlighted the limitations of nation-states in offering asylum and many years later philosopher Giorgio Agamben too has observed the fundamental inefficiency of states to absorb the stateless. Rather they will try to concentrate refugees in designated areas, in other words, camps or detention centres. While on the one hand there have been large scale movements demonstrating sympathy there have also been demands to fortify boundaries and expel the aliens. There is a greater need for us to uphold Arendt’s idea of “the right to have rights”: the right to belong to political communities and to participate in their social practices. She argues for the rethinking of the nation-state to overcome this limitation and invent a democracy which is not bound by territoriality. The slowly marching figures in Sudipta’s exhibition implore us to be a part of this rethinking because the conventional ideas of inclusion and integration are not enough. Rather we should reorganize states to adapt to this global aterritoriality of the refugees. They call for new models of citizenship especially Aihwa Ong’s notion of flexible citizenship which allows people to choose to the political communities they want to be a part of according to the desires and interests.

Recently specialists have coined terms such as “climate change refugees” to denote the millions who leave their homes due to climate change or “climate vulnerable” to describe those communities or nation-states that have a particularly acute vulnerability to present and forecasted climatic changes. The 2018 estimate of World Bank forecasts that three regions, i.e., Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia will generate 143 million climate refugees by 2050. Despite these warnings governments across the world have not drafted any kind of policy that offers asylum to these victims. In India too, we lack any consolidated statistics about the numbers of people displaced due to natural disasters. Though the government agency National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) has identified floods and droughts as a major reason for migration there is a lack of engagement at the policy level to accommodate and recognize them. The “wanderers” remain invisible for the politico-legal institutions and ultimately detention centers and camps become the burial grounds for these people who fled for their safety.

Sudipta is inspired by the dakjee doll making technique learned while on residency in Korea in 2017. Her use of paper and the fragility of this medium catalyses an important discussion towards the precarious condition of climate change refugees, especially in the context of the Citizenship Amendment Act and the National Register of Citizens. The NRC in Assam has put the onus of proof on each and every one. It is the people who have to prove that they are citizens by producing kagaz or documents. Therefore, in Sudipta’s work paper itself has become a metaphor for the fragility and vulnerability of the refugee. The tone of the exhibition is empathetic, Sudipta aims to raise awareness about the vulnerability and fragility of lives of people who are force to migrate. Her exhibition opens at a crucial time when the word refugee has become a polarizing term in both international and national politics. At the national level the NCR threatens to exacerbate the misery of millions of vulnerable lives rendering ever greater number of people disenfranchised. Although they appear solid, the exiled body of Sudipta’s refugee is built on the vulnerability of a perishable medium. These figures are as fragile as the documents that bind citizens to their nations. Yet, they commence their journey to be thrown under the weight of new political discourses and crushed under the heavy boots of rigid laws that cast them into a never-ending legal limbo.

Renowned Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, who has written extensively on the idea of exile has observed that “Exile is more than a geographical concept. You can be an exile in your homeland, in your own house, in a room.” Sudipta locates this entrapment, anxiety, and helplessness in the bodies of the refugees. Under the current circumstances the refugees are fragmented and their lack of political consolidation necessitates the question that how can they overcome their political despair? Will their exodus ever come to an end? Will they return to their homeland and be able to restore it?

These small bodies evoke a non-violent language of consciousness and through them, Sudipta urges us to recognize them as fellow human beings so that we both can share conversations with each other instead of being hostile. Sudipta’s representations of the victims of climate disaster attempt to strike the collective conscious and pleads to the empathy of the viewers. This immersive exodus of eternal wanderers speaks to our sense of justice to the precarious lives and asks us to imagine a politics of asylum. It asks us to equate people who land on our shores due to natural disaster with those who escape political persecution. We need to abandon our existing lexicon of fences, camps, and other forms of detention which dominate our contemporary political parlance. Across the world, walls are raised to stop sea levels and incoming refugees, they are build to cordon off areas as as detention camps. The climate refugee or climate vulnerable is not merely a victim of natural disasters. These are also political disasters in which the citizens from developing nations bear the brunt of disasters created by the developed nations. Our planetary future is at stake with the weakening of political pluralism, civil society, democratic institutions and freedom of expression. Sudipta encourages us to imagine a planetary politics which seeks justice to the past displacements and the future of existence. This exhibition allows us to imagine a movement oriented political vision. It argues that human beings have always been wandering and migratory. The modern territorial oriented political dimension has delegitimized migration. Sudipta’s works emphasizes that, we require newer paradigms that recognizes the humanitarian crisis brought about by climate change.