Pareidolia: Songs of (Dis)Belief

Aug 24, 2022 - Oct 5, 2022

- SELECTED WORKS

- CURATORIAL NOTE

- INVITE

- PRESS RELEASE

““The order that our mind imagines, is like a net, or like a ladder, built to attain something. But afterward you must throw the ladder away, because you discover that, even if it was useful, it was meaningless.”

– Umberto Eco, The Name of the Rose

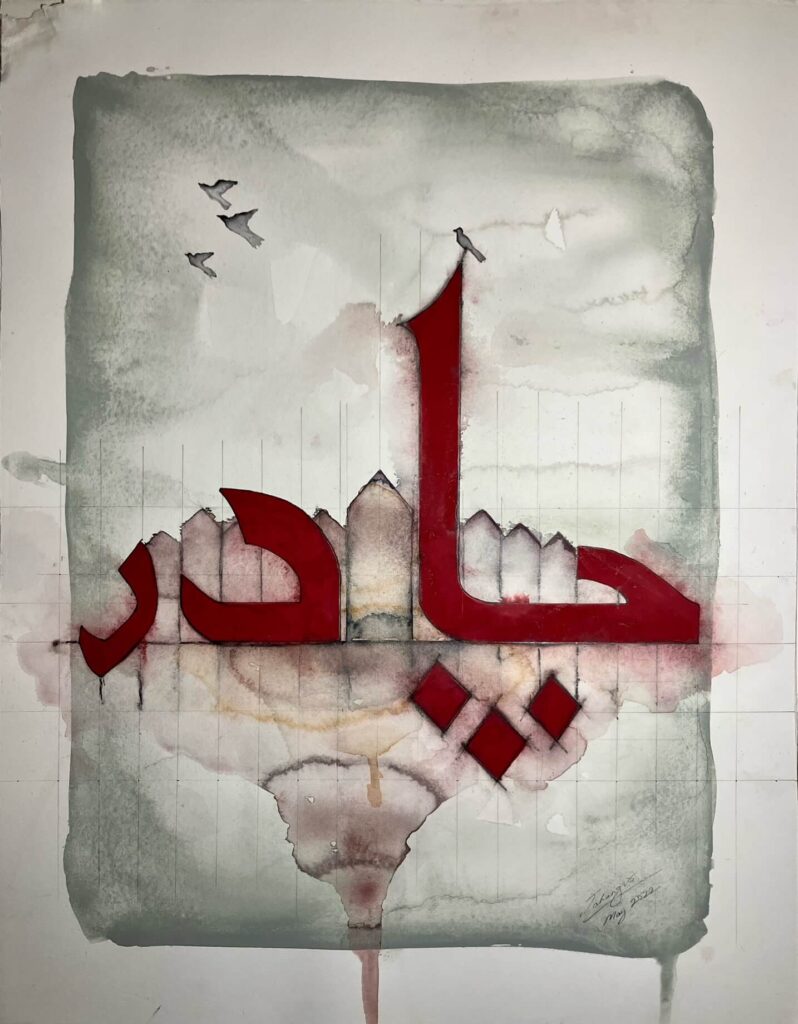

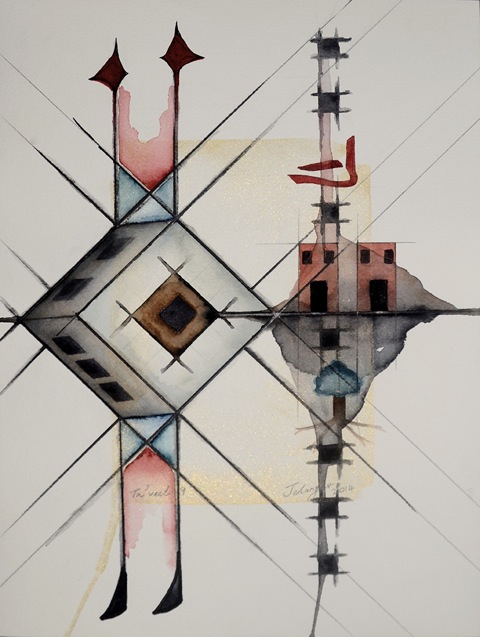

Somethings are understood by instinct, and others are learned comprehension. While some symbols are instantly recognisable, do they always mean what you think they mean? Just as all cyphers cannot be cracked with a singular code, Jahangir Asgar Jani’s watercolours are not to be deciphered with a single lens. Perhaps this search for meaning lies in the past, in the depths of memory, or in the folds of time? That is, if one believes in meaning at all. ‘Pareidolia: songs of (dis)belief’ asks you, the viewer, to shed preconceived notions as you navigate Jahangir Asgar Jani’s watercolours.

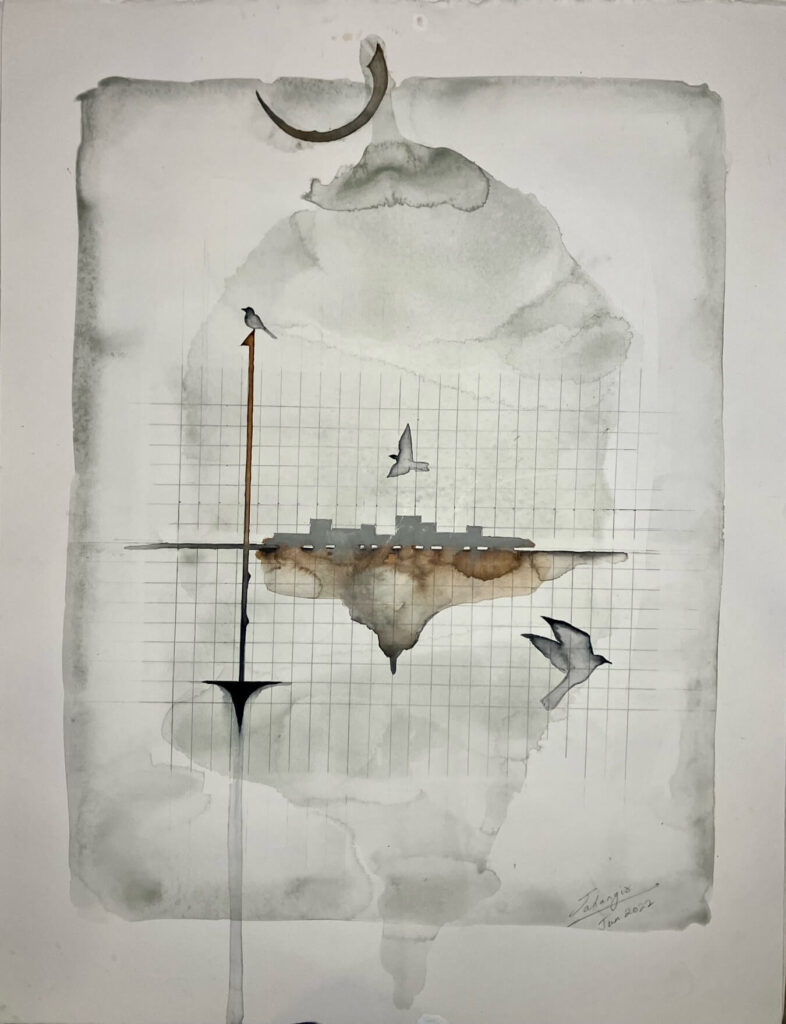

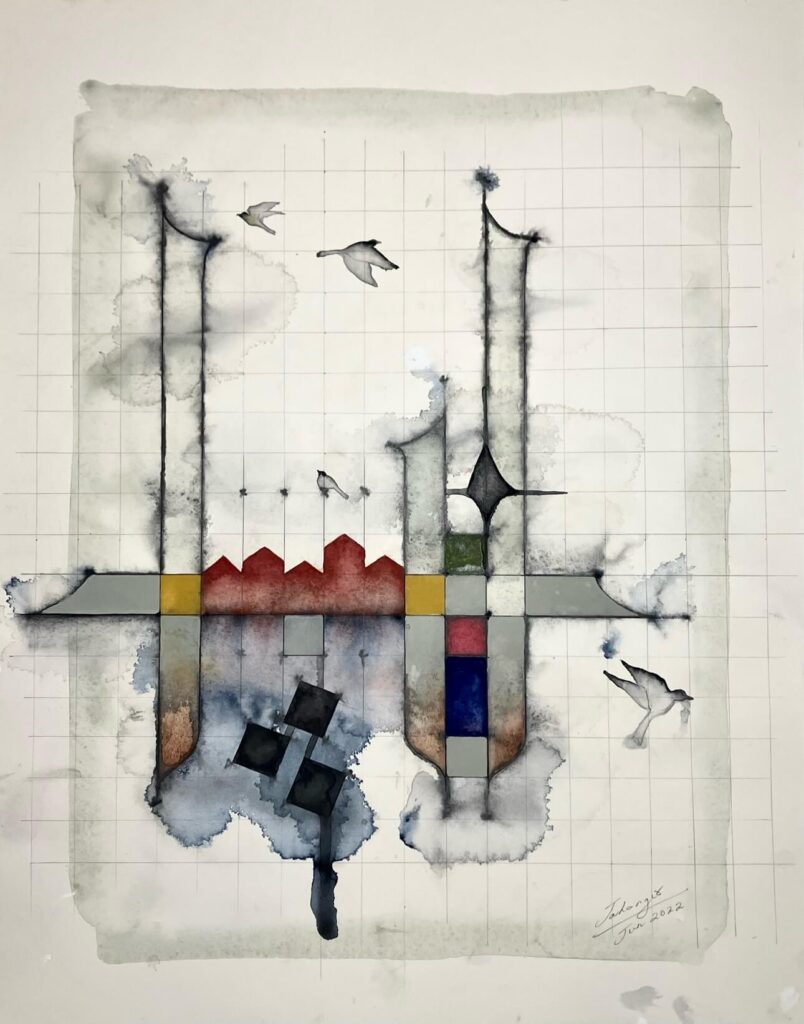

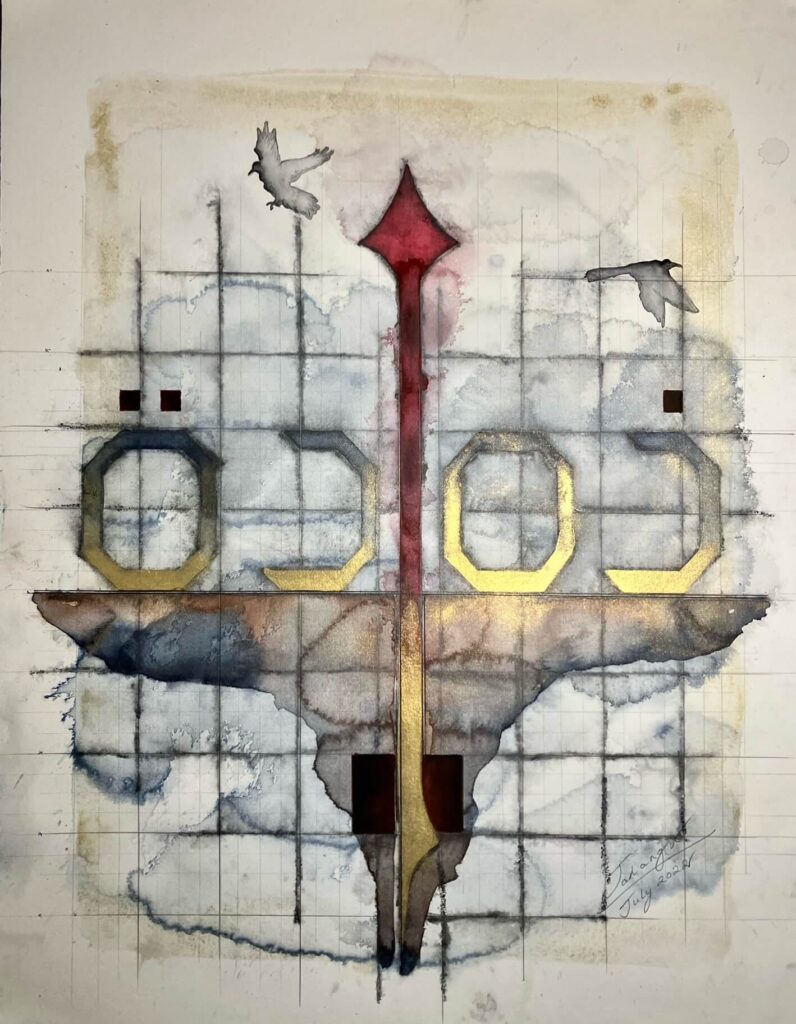

Stepping away (briefly) from making sculptures, the medium of watercolours has allowed Jani to play with light, and create works that seem fluid and ephemeral. The sharp confidence of each line is diffused by the pale translucence of watercolours. However, each image reveals a grid which gives the work a robust structure. Thus framed, but not constrained, calligraphy and architectural form overlap, and around them, birds fly, soaring and diving, unrestrained. Perhaps messengers or symbols of the soul or simply visual devices to draw the eye, the interpretation of birds, depends on the viewer’s own structures of belief/disbelief.”

– Excerpt from the curatorial note by Aparna Andhare

CURATORIAL NOTE

PAREIDOLIA: SONGS OF (DIS)BELIEF

Recent Watercolours by Jahangir Asgar Jani

“The order that our mind imagines, is like a net, or like a ladder, built to attain something. But afterward you must throw the ladder away, because you discover that, even if it was useful, it was meaningless.”

– Umberto Eco, The Name of the Rose

Somethings are understood by instinct, and others are learned comprehension. While some symbols are instantly recognisable, do they always mean what you think they mean? Just as all cyphers cannot be cracked with a singular code, Jahangir Asgar Jani’s watercolours are not to be deciphered with a single lens. Perhaps this search for meaning lies in the past, in the depths of memory, or in the folds of time? That is, if one believes in meaning at all. ‘Pareidolia: songs of (dis)belief’ asks you, the viewer, to shed preconceived notions as you navigate Jahangir Asgar Jani’s watercolours.

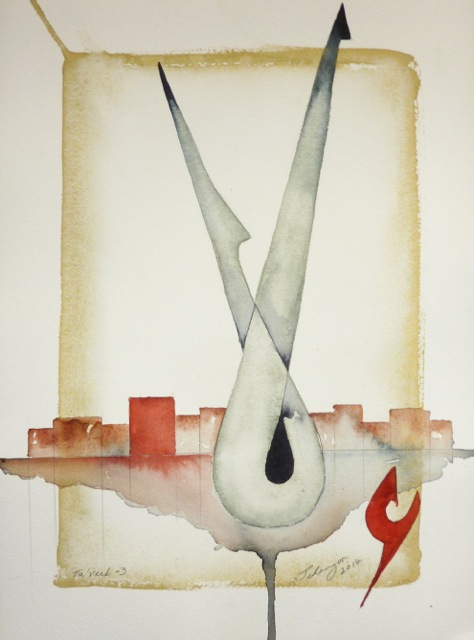

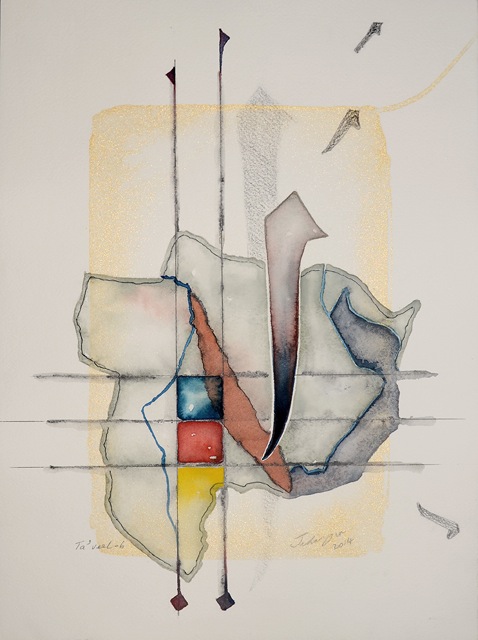

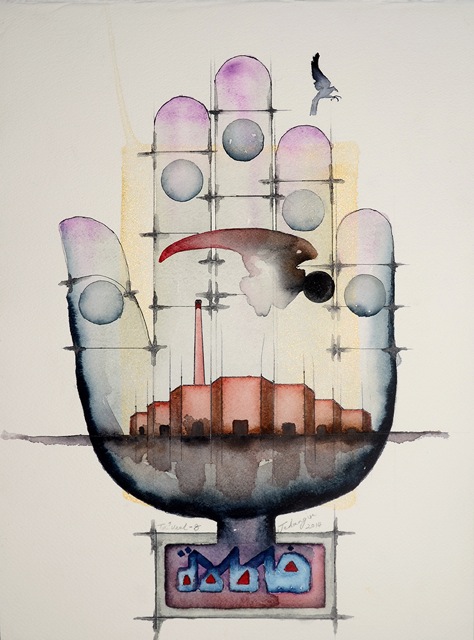

Stepping away (briefly) from making sculptures, the medium of watercolours has allowed Jani to play with light, and create works that seem fluid and ephemeral. The sharp confidence of each line is diffused by the pale translucence of watercolours. However, each image reveals a grid which gives the work a robust structure. Thus framed, but not constrained, calligraphy and architectural form overlap, and around them, birds fly, soaring and diving, unrestrained. Perhaps messengers or symbols of the soul or simply visual devices to draw the eye, the interpretation of birds, depends on the viewer’s own structures of belief/disbelief.

Creating a dream-like atmosphere, the terrain is cloudy and perspectives shift with remarkable ease. Is it an urban landscape, or monumental calligraphy? The representation of a fast changing world, or a fantastical landscape where writing and drawing merge? When do alphabets become words? When do scribbles and markings on the page become writing, and start to make sense? Since the relationship between script and language is one that Jani has closely observed, and he is able to deconstruct words and motifs from religious associations, making charms and amulets that protect as much as they provoke. The Panja (a sacred handprint), for example, is now more than a talismanic device and contains multitudes of stories within it.

For Jani, it is evident that the world is constructed with form and words, both of which are malleable on sheets of paper. His work invokes Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, where Marco Polo says: “Cities, like dreams are made of desires and fears, even if the thread of their discourse is secret, their rules are absurd, their perspectives deceitful and everything conceals something else […].” What rules apply to the arches, the tall towers and subterranean landscape in Jani’s work? Just as a master calligrapher privileges aesthetics and symmetry, and relies on the viewer to know where the nukta (diacritic mark) ought to be placed in order to be able to read, Jani trusts the viewer to read his Verses.

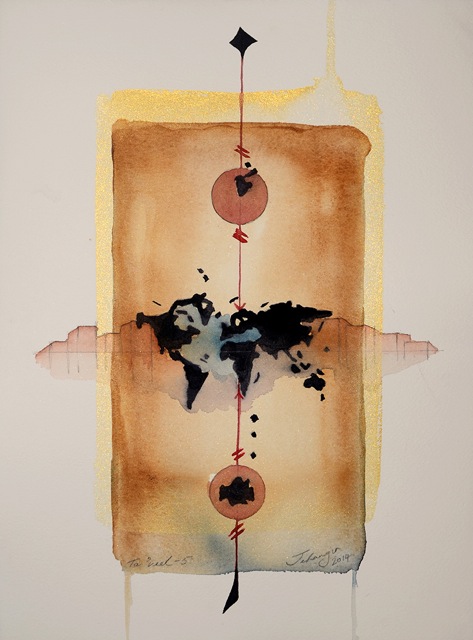

By flattening the globe, ironing out the creases of the map of the earth while integrating the form of the globe in Ta’aveel (5), Jani spells out the scope of his engagement: this work is not rooted to a particular geography, or Islamic theology, but exists in a wide spectrum. There is no tension between word and image in Jani’s world but a coexistence, and an open-mindedness towards interpretation. His voice is a faint but firm whisper, heard through indications, subtle nudges and suggestions but without insisting upon a singular point of view, or asserting a fixed meaning. In creating space of dialogue, a place for belief and room for disbelief, the artworks in Jani’s Pareidolia manifest unique patterns, which range from protest to despair, from hope to celebration, poetry to prayer. Fragmented but not broken, the spiritual and the mundane sit comfortably together, as do natural forms and man-made constructions. The artworks create a world where poetry is insinuated rather than recited, understood rather than expounded. Comprehension hangs on a thread of belief, of devotion, and in the same way, on skepticism.

Jani is on a search for meaning, and attempts to trace the roots of implicitly knowing, and acquired knowledge. The artist has left a series of clues for the viewer, some disjointed, others distracting, and he lets you find your own language to decipher messages. The line from Antoine De Saint-Exupéry’s classic The Little Prince resonates perfectly: L’essentiel est invisible aux yeux (What is essential is invisible to the eyes.) In Pareidolia: songs of (dis)belief you have to choose what you see, but with more than just your eyes.

By Aparna Andhare