If a Tree Falls (Somewhere in Northeast India)

Mar 25, 2021 - Mar 31, 2021

- SELECTED WORKS

- CURATORIAL NOTE

- REVIEWS

- INVITE

- PRESS RELEASE

- DOWNLOAD CATALOGUE

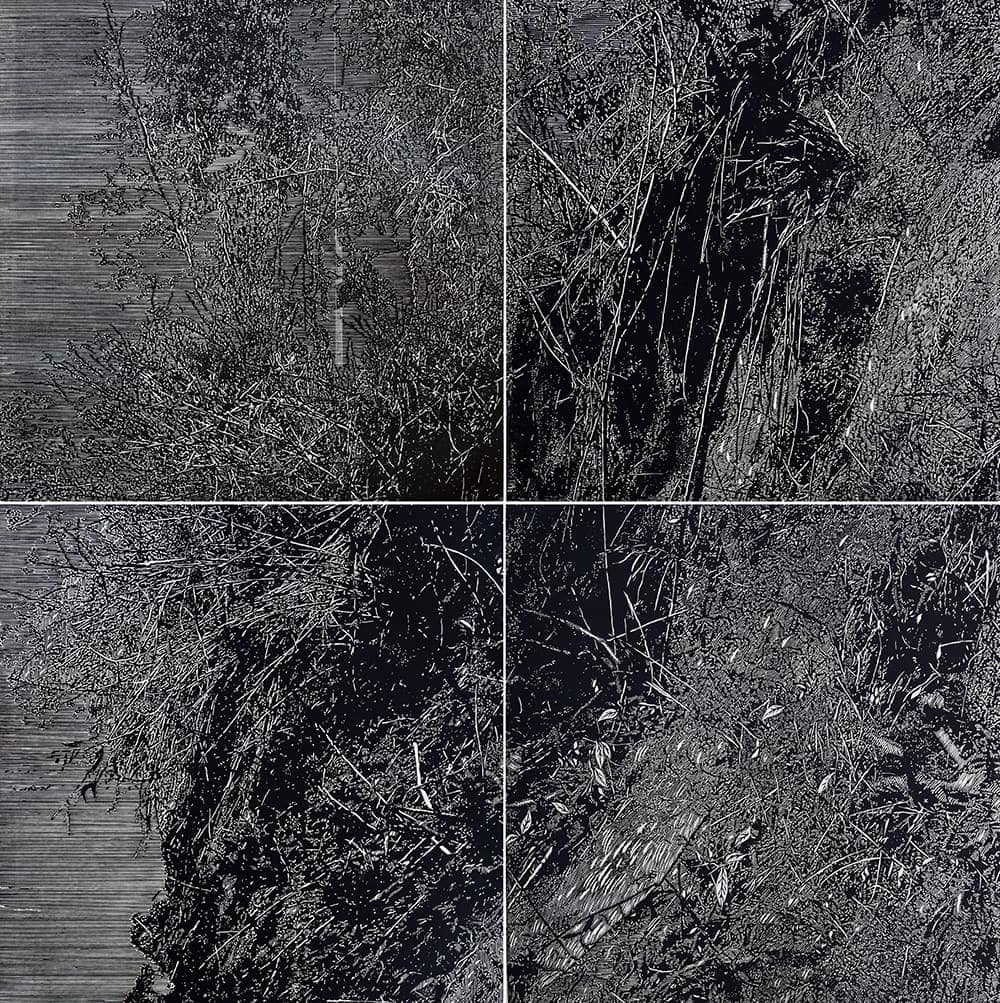

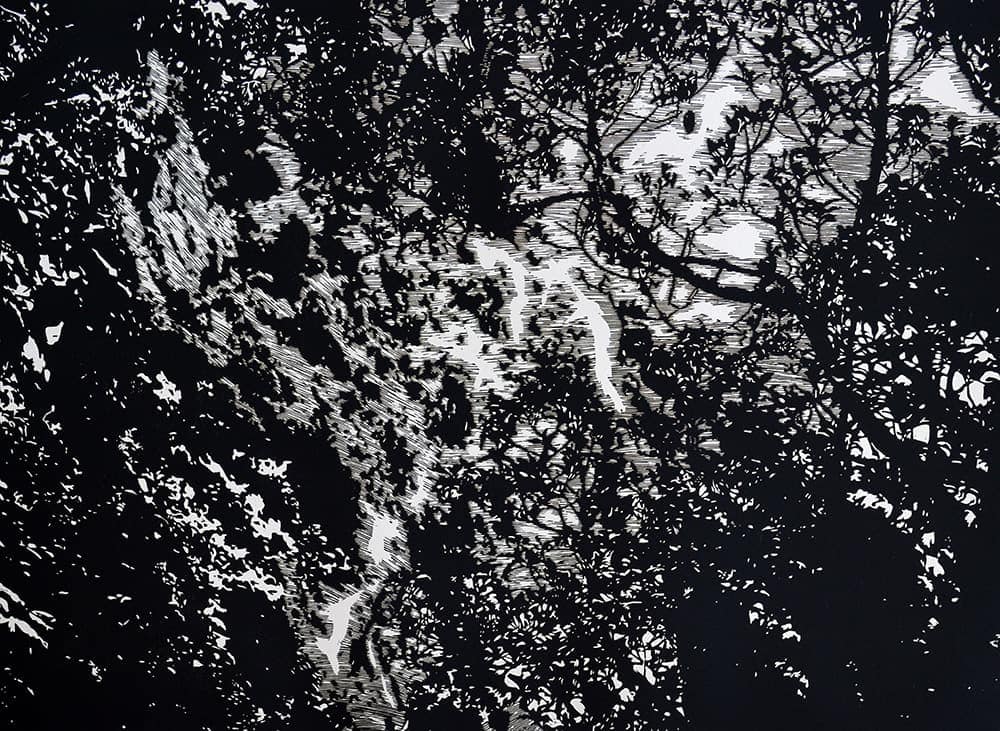

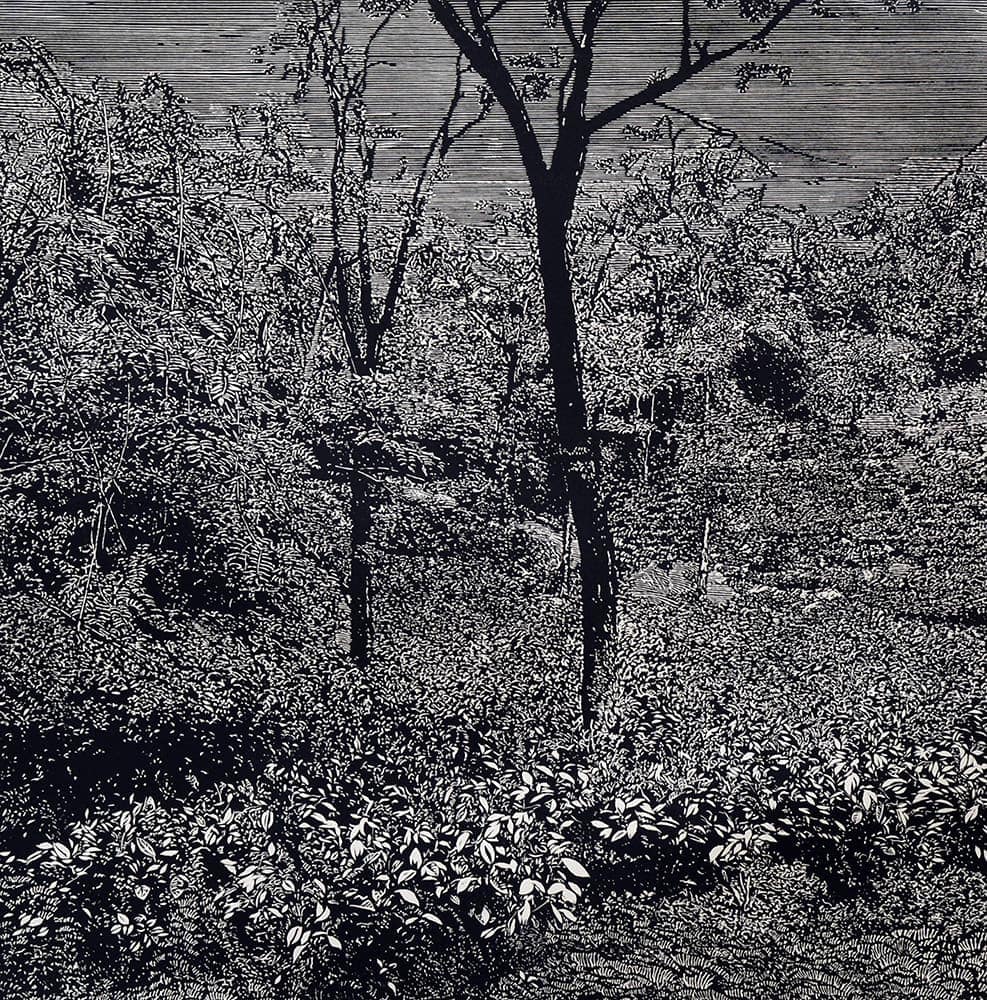

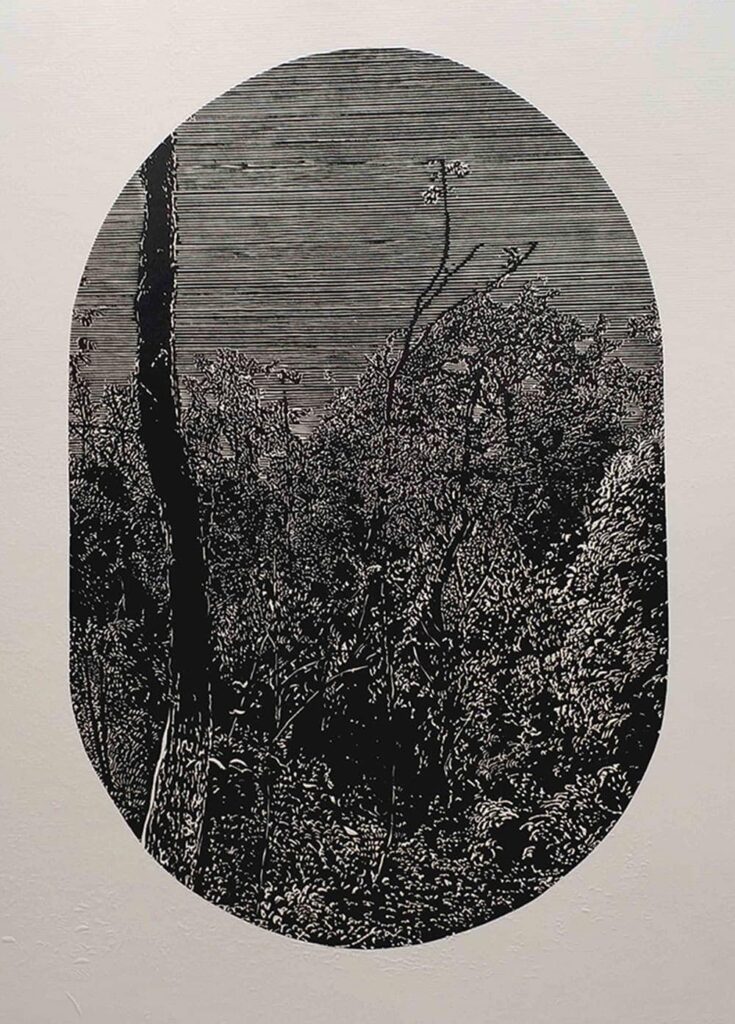

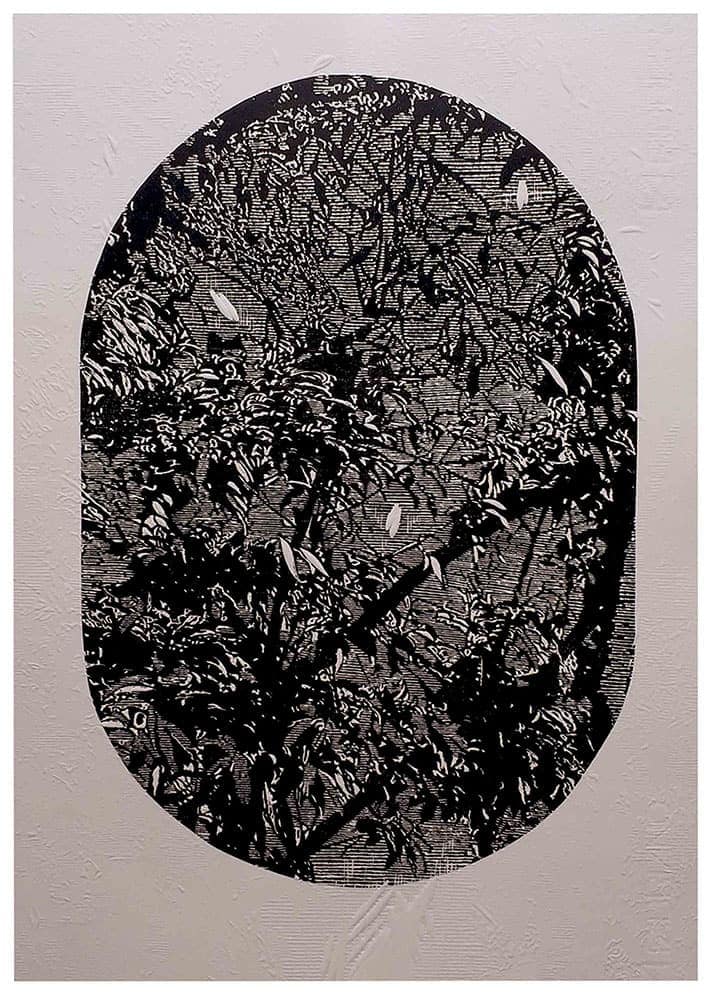

‘If a Tree Falls (Somewhere in Northeast India)’, a show that features recent works by Chandan Bez Baruah curated by Waswo X. Waswo. There is an intimacy to these images, as if the artist has trekked us through the jungle to his most favoured haunts, asking us to stay silent and observe what he treasures and wishes to reveal. The artist has skillfully coaxed these images out of wooden boards because the woods itself is asking for revelation. We are seeing things from Chandan’s eyes – the young man who once conversed with these woods and walked in step with Indian soldiers he would befriend as similarly needing a desi pair of eyes.

CURATORIAL NOTE

If there be no ears

“Sound is vibration, transmitted to our senses through the mechanism of the ear, and recognized as sound only at our nerve centres. The falling of the tree or any other disturbance will produce vibration of the air. If there be no ears to hear, there will be no sound.”

-from a controversial article in Scientific American, April 5, 1884

Chandan Bez Baruah was born in Nagoan, the fourth largest city of Assam, which is cut through its border by the Kolong River, a tributary of the Brahmaputra. Indigenous Assamese communities such as the Karbi and Tiwa (Lalung) are natives to this city, which is also home to twenty-five colleges and the rich spiritual and cultural tradition of Bhaona, a mythology-based live performance that enthralled the artist in his youth. When Chandan was in fourth standard, his mother tragically passed away, causing the remaining family to shift to Guwahati, the state’s largest city, which is bordered by the Shillong plateau and the Amchang Wildlife Sanctuary. Guwahati is also divided by a river, the Bharalu, also a tributary to the Brahmaputra. It was in Guwahati that Chandan developed a keener love for the forests, seeing them as an escape from the congestion of the city and a soothing retreat in a time of newfound loneliness. He says, “When I lost my mother, at an early age, I was deeply disturbed and depression was always with me. When we shifted to Guwahati city, I became lonely. The whole of Guwahati city is surrounded with hills, and my home also was near the lower end of the hills. I used to go to the green jungle more than entertainment or other activities. In the midst of the jungles, I talked with them. I enjoyed my talks with the jungles more than my friends.”

In 1669, Andre Felibien, the secretary to the French Academy, declared in his Preface to a series of published lectures a hierarchy of painting genres that he felt had become evident since the Renaissance, with the most respected form being history painting, followed by portrait art, genre painting, landscape and still life (in that order). This valuation of forms followed the primacy that Greek aesthetics gave to the human body, especially the nude. Unlike Chinese art, which nurtured a landscape tradition beginning in the fourth century CE, landscape as a genre did not exist in Western art until the Renaissance. Indian traditional paintings were devoid of landscape, except as background for historical and religious depiction. Oddly, this devaluation of the landscape is perpetuated in today’s Postmodernism, which is inclined to deconstruct traditional landscape art as romantic nostalgia at worst, or expect from it visual criticisms of the Anthropocene at best.

In a rambling (and ultimately self-rejected) concept note to his series Somewhere in Northeast India, Chandan had opined that one purpose to his landscapes was “to see the insight terrain of the marginalised or the subaltern, and to situate Postmodern landscapes as encountering Romantic theory”. The truth of Chandan’s statement is evident when looking at the work. Meticulously carved upon medium density wood-fibre matrixes, these woodcuts nonetheless spring from the digital photographs which Chandan has earlier captured for reference. The artist’s inspired translation of these photographs, and highly skilled hand-craftsmanship, is astounding. The photorealist style he painstakingly employs is complicated by the chaos of the scenes; a chaos unlike the orderly compositions one might expect in more traditional and Pictorialist vocabularies, yet which holds a graphic beauty of its own. Devoid of human figuration or wildlife, Chandan unashamedly subscribes to the notion of the solitary observer, or, as the American photographer Ansel Adamas once put it, To the complaint, ‘There are no people in these photographs,’ I respond, ‘There are always two people: the photographer and the viewer.’

Yet, there are many more than two people in these woodcuts. There are multitudes. Chandan’s stark, mountainous undergrowth exists within ecologies and geographies of history, culture, and contemporary conflict. Above and beyond these wooded hills floats our awareness of current debates: illegal immigration, the National Register of Indians, The Citizenship Amendment Bill, the threat of Palm Oil production, environmental destruction, authoritarian right-wing politics, communal divides, and also liberal misunderstandings, overreach and complicity. The silence that is implied in these images is not just the silence of a beautiful stillness, nor the transcendental hush of the cosmos we might imagine they conjure, but the silence of the marginalized, the guilty, and the afraid to speak. Art conveys that which cannot be articulated. Chandan fuses spiritually romantic longings for beauty, solitude, and the sublime, with a postmodern awareness of chaos, politics, and lived experience. If there is any doubt of the artist’s awareness of politics, one only needs to refer to his earlier series, Behind Me, with its graphic foregrounding of ordered military troops, barbed wire, and martial power.

The artist has skilfully coaxed these images out of wooden board because the woods itself is asking for revelation. There is an intimacy to these images, as if the artist has trekked us through the jungle to his most favoured haunts, asking us to stay silent and observe what he treasures and wishes to reveal. We are seeing things from Chandan’s eyes – the young man who once conversed with these woods and walked in step with Indian soldiers he would befriend as similarly needing a desi pair of eyes. Chandan has heard the songs of birds, the peep of frogs, the swift clicking buzz of beetles and the rustle through the leaves. He has heard trees falling in the forest. He asks us to use our eyes as ears, and hear their falling, too. Be a witness. It is only the act of hearing that makes these fragile treescapes real.

Waswo X. Waswo

Udaipur/ 2020